Types of Jobs

In the spring of 1942, more than 2,000 able-bodied Japanese Canadian men between the ages of 18 and 45 were separated from their families and sent to Interior BC road camps to work on federal Department of Mines and Resources road construction projects. Many were young single men, but married men with families were also conscripted. Read more about the road camps

By March 1942, the Hope-Princeton Highway construction project employed over 1,000 men who lived in five road camps along the route from Hope to Princeton. Most of the families of these men were sent to Tashme. In July 1943, the regulations were changed to allow the men to join their families.

The BCSC and later the Japanese Division of the federal Department of Labour were the employers of the interned Japanese Canadians. By January 1943, about 600 men and women were on the BCSC payroll and fewer than 100 men and women were on maintenance relief. About 35 Caucasian workers were hired by the BCSC for camp operations, mainly in supervisory positions.

After the initial building phase was complete, many Japanese Canadians were hired by the BCSC as office workers, hospital workers, farmers in the extensive vegetable gardens and livestock barns, teachers, shop workers, municipal services workers, etc. The general store hired 40 Japanese Canadian women as sales and clerical staff.

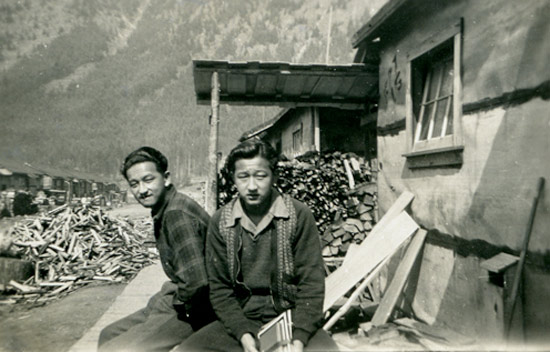

The Tashme sawmill hired men to produce materials for the construction of housing for the residents and village buildings and for the remodelling of existing farm buildings into schools and apartments. In August 1942, 350 men were employed to build 347 houses and other construction projects. In March 1945, the sawmill employed 212 men. The total number employed in Tashme was 645[u1] and the monthly payroll was $34,883.

A Fuelwood Project was undertaken in the summer of 1943 at the request of the Wood Fuel Controller of the Department of Munitions and Supply to aid in averting a critical fuel shortage in Vancouver and other BC cities.

Other men were employed at a second sawmill, located a few miles away, owned by Peter Bain of Haney. The wages at this mill were higher than at the BCSC sawmill. Some boys, mostly between 16 and 20, worked on gravel and logging trucks as "swampers." Still other men and high school boys, who worked only until 3:00 p.m. so they could attend high school classes in the evening, worked in the store, office, and shops. Some worked in the fields and farm, which grew carrots, celery, and cabbage for the store, and oats for the horses.

NNM 2015.8.1.1.053.

Girls were employed as teachers, stenographers, and clerks in the office, clerks in the stores or warehouse, and nurses' aides in the hospital.

One of the primary purposes of the Japanese Division of the Department of Labour was to find employment for all employable Japanese Canadians. Once the immediate goal of finding employment for all internees in the road camps and the BC internment camps had been met, effort went into finding employment for young single people east of the Rockies, to meet Canada's need for manpower in essential industries. Younger road camp workers were offered jobs in forest operations and farming mainly in Alberta, Manitoba, and southwestern Ontario.

As in many internment camps, Tashme residents were encouraged to have private garden plots and were given free seeds and the use of implements. The BCSC operated substantial farms at several camps employing about 100 Japanese Canadians.

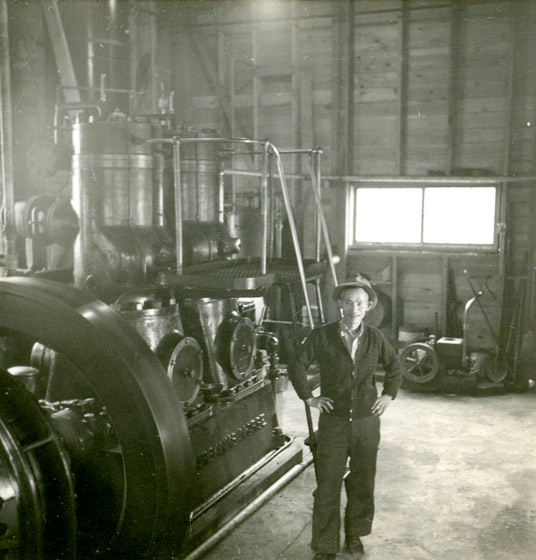

In 1943, the BCSC established a small shoyu and miso factory in Tashme. Mr. Shinichi Negoro, who had skills and experience in shoyu and miso paste production, was in charge of the operation and the Japanese Canadian staff. The factory successfully produced high quality products not only for Tashme but also for export to other internment communities and Japanese populations east of the Rockies.

Rates of Pay

Japanese employees were paid a basic wage of 25 cents per hour, although specialized workers earned more. (The average wage in Canada in 1942 for men was 62 cents per hour; for women, 37 cents per hour.)

Road camp workers were paid 35 cents per hour. The minimum wage for common labourers was 25 cents per hour for an eight-hour day, less 2.5 cents per hour taken off for shelter. Single men earned 17.5 cents per hour net plus board. Skilled labourers, carpenters, plumbers, mechanics, etc., earned 22.5 to 27.5 cents net per hour; some who supplied their own tools earned 37.5 cents net per hour.

Japanese Canadians employed as construction and maintenance men, fuel cutters, etc., on outdoor work earned from 22.5 cents to 40 cents per hour. Until April 1, 1943, professional and inside employees were paid partly hourly and partly monthly; after that, they were paid monthly at rates ranging from $30 to $75 per month. An exception was doctors and dentists, who received more.

Maintenance for the Unemployed

The BCSC supported people who were not employed, since they had been exiled by government decree as a military necessity, and thereby forced to relinquish their homes, jobs, and lives. These included the sick and physically unfit, the elderly, single parents, and others unable to work, or whose work income was insufficient. ,

A welfare department was established within the BCSC under the management of a trained social worker. Its responsibilities were to ensure that maintenance was given to those eligible in accordance with policies that were already in effect in BC. It provided financial support, as well as housing, food, and clothing. Tashme, like the other internment camps, had a welfare department with a manager and Japanese Canadian staff who maintained contact with individual families. Its chief responsibility was to issue full and supplementary maintenance at the provincial relief rate.

In 1942, people on maintenance relief received $15 per single person, $11 per person per month for two persons per family, and $4 per additional family member per month. A family of four received $30 per month. Shelter, water, wood for heating and cooking, and coal oil for lighting were also provided[u2] .

When the men from the road camps were allowed to rejoin their families in Tashme and were put to work building shacks, the number of families needing welfare lessened. Also, the road camp workers had to pay for their families’ keep out of their wages. The BCSC payment system essentially redistributed the internees’ own funds.

Tashme Voices

So why were the Negoros the last family to leave Tashme? My father got together with a group of entrepreneurial Japanese Canadians, including Mr. Steve Sasaki, a Judo fifth black belt sensei, Mr. Arthur Nishiguchi, Mr. Magojiro Nishiguchi, and Mr. Suzumoto. They planned to set up a shoyu/miso factory in Ashcroft where these men resided. The group had purchased the raw inventory left over from the Tashme factory which was decommissioned about the time the ‘repats’ were sent to the port of Vancouver for transfer to Japan in 1946. We were in the process of filling large barrels with soya beans when the RCMP and administrators vacated in the fall of 1946. My father did not sign up to go to Japan, so we were the last ones left to fend for ourselves. Mr. Arthur Nishiguchi had a one-ton boxed trunk which he drove in with Mr. Sasaki, son Kiichi Nishiguchi and nephew, Kaichi Nishiguchi. We loaded up the truck along with our meagre household effects and with mom, Mr. Sasaki, my sisters Emi and Shigemi in the front seat, the rest of us with dad holding Kazumi, rode the tailgate, making our way slowly down to Hope. This would have been around the 4th or 5th of November 1946, a few days before my twelfth birthday. From Hope, we caught the train to Ashcroft. – Tak Negoro