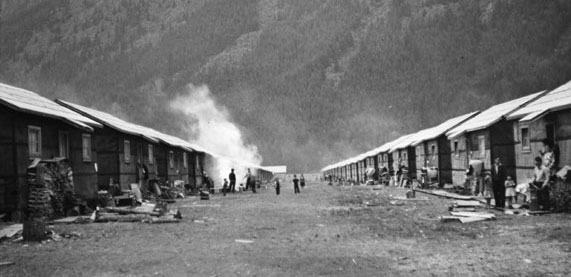

Imagine building a community of 2,600 persons from scratch. Once people’s basic housing and survival needs are met, how would they organize and govern themselves? How would they educate their children? How would they provide for their health care? How would they secure funds to meet the demands of daily life?

The residents of Tashme quickly realized that they had to work closely with the BCSC supervisors and staff, and they had to organize services for themselves. They did so efficiently and with a deep sense of community.

Governance

Despite the fact that Tashme was formed through the forced relocation of its residents, the camp functioned with a high degree of order, peace, and efficiency. The overall supervision and administration of the camp fell to the British Columbia Security Commission, during both the initial construction, settlement and after. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police enforced law and order in the camp. Residents took responsibility for their own internal regulation by forming the Shinwa-kai, a committee to oversee civic affairs within the community. A combination of municipal council, liaison with the BCSC, and proponent of community well-being, the Shinwa-kai became an essential force in the life of Tashme. The internees kept up on local news by means of a portable bulletin board called the kairan-ban. READ MORE

Tashme Voices

On that last day of October 1942, soon after my arrival in Tashme, I attended a small gathering brought together by Miss Hide Hyodo, Terry Hidaka and other educators. This meeting was convened to provide school age children with a place to continue their learning. From this modest gathering, classes were started shortly thereafter in what had been a huge old barn. Portable wooden panels were erected to divide the elementary grade classes. Japanese men handmade the wooden desks and benches to seat two pupils. Upon opening the big barn door for start of classes, the sound of pupils and movement emanating from inside could be intense at times! – Marie Katsuno

Policing

Hope, being located within the 100-mile protected area, was “off-limits” to us. There always was an RCMP officer on guard at the camp gate to check all incoming and outgoing traffic.

From Teaching in Canadian Exile Moritsugu and Ghost Town Teachers Historical Society, p. 189.

Tashme, like the other internment communities, was policed by members of the RCMP. Besides performing their normal police duties, the RCMP officers were responsible to the BCSC to observe the movements of all internees and to ensure that the rules and restrictions set out by the BCSC were observed. They maintained a post at the entrance to Tashme to monitor movement in and out of the camp.

The RCMP detachment was housed in a small building located in the Tashme town centre. The building was equipped with an office and a jail cell.

The RCMP conducted regular patrols to ensure that law and order was maintained. The most serious cases they had to handle were disputes, usually verbal disputes. In addition to regular police work, the RCMP was responsible for preparing a monthly report, which included a census of the population. They also kept a record of vital statistics.

In the beginning of the internment, travel by Japanese Canadians was restricted. To travel, they had to show an adequate reason before the RCMP would issue a travel permit, for example, the death of a relative.

The RCMP constables were well respected by the community for their vigilance, fairness, and courtesy.

The RCMP was responsible for carrying out administrative orders issued by BCSC that controlled the movement of Japanese, surrender of certain possessions, restrictions on use of cameras, radios, and on local fishing, hunting and trapping activities, and communications by long distance telephone. Many of these orders were modified or restrictions relaxed during the course of internment as conditions changed.

From Dept of Labor Report on Administration of Japanese Affairs in Canada 1942-1944.

Kairan-ban

Tashme residents created the kairan-ban, a portable bulletin board that was passed from door to door. It was used for communicating news, advising residents, or making requests of members of the community. The kairan-ban would begin its journey at the first house in each avenue and be passed along with minimal delay so that any news would be disseminated quickly. Residents were asked to initial or sign to indicate that they had read the news before passing the kairan-ban to the next house.

The kairan-ban was at once a message board and a newspaper for the community. It was an effective way of quickly communicating important messages, news of upcoming events or happenings in the community, or information of interest such as new shipments of goods available at the general store. It worked well because of the orderly layout and close proximity of the houses.

Employment

The internees lost their jobs and livelihoods when they were relocated from the coast. Although the BCSC took responsibility to support individuals and families where necessary, government policy decreed that people support themselves through employment to the greatest extent possible.

Because Tashme was purpose-built and self-sufficient, employment was plentiful. The BCSC and later the Japanese Division of federal Department of Labour was the employer of the interned Japanese. Residents worked at a variety of jobs, from road camp labourers to doctors and dentists, and everything in between. READ MORE

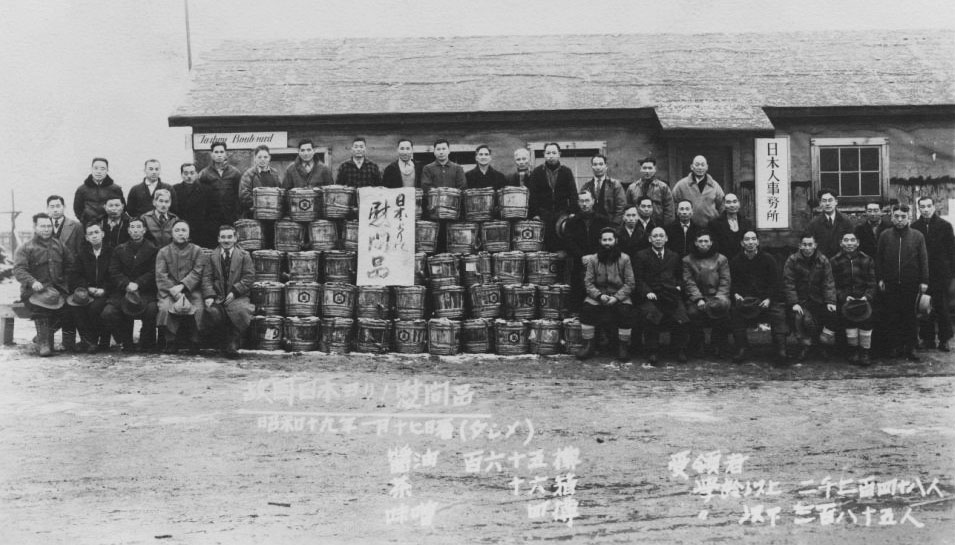

Shinwa-kai

Among the camp residents, as in any large group of people with common values, civic affairs were an important part of community life. While in Hastings Park, awaiting relocation to Tashme, the internees elected a construction committee to reflect their needs during the relocation and adjustment to life in Tashme.

On December 7, 1942, a 50-member committee was elected from among the residents of Tashme, replacing the construction committee. This committee adopted the name Shinwa-kai, meaning "harmonious alliance." The Shinwa-kai representatives were elected every six months from each avenue and the apartments.

The Shinwa-kai worked with the BCSC to establish policies and rules and lobbied the BCSC to improve conditions for residents. It acted as a bilingual liaison between the BCSC and the community, and operated as a municipal council in setting and policing rules.

The Shinwa-kai accepted responsibility for most of the internal affairs of the community. It looked after the delivery of wood for heating and cooking and coal oil for lighting, garbage disposal, and the maintenance and repair of houses, roofs, and stoves. It established the kairan-ban, a community bulletin board that was passed from house to house to communicate news and information quickly. It selected an executive committee to manage such issues as education, welfare, prices, sports, and recreation.

Known for great organizational skills, the Shinwa-kai assured that camp morale was high, that everyone was occupied and contributing, that youth were not idle, and that women were learning new skills. It also took care of funerals and cremations, and communications among residents.

Residents would bring their problems and grievances to the Shinwa-kai for resolution. After a full discussion, the Shinwa-kai would take issues to the proper channels such as the BCSC. The Shinwa-kai exerted a strong influence on the Japanese community.

Excerpt from a report about improvements negotiated by the Shinwa-kai

Article from the New Canadian on the town names list compiled by the Shinwa-kai

Education

The forced removal abruptly interrupted the schooling of Japanese students. Although the education of all children in Canada was a provincial mandate, the government of British Columbia argued that the education of Japanese Canadian children was no longer its responsibility because the relocation was a federal mandate. During the period of relocation and dispersal, no provincially qualified teachers were available to teach the interned students. The Department of Education refused to hire teachers for a short period of time. In the fall of 1942, it looked as if Japanese children would not be educated. READ MORE

Health Care

At first there were no medical facilities at Tashme. A temporary clinic was set up while a hospital was built. Although the hospital initially was headed by a series of Caucasian physicians, Tashme was fortunate to have the services of several Canadian-trained and qualified Japanese doctors and nurses. Medical services ended at Tashme in June 1946. READ MORE

Religion

Although there were three religious denominations in Tashme – Buddhist, United Church and Anglican Church – the main religious distinction was not denominational but rather Buddhist and Christian. The majority of residents were Buddhists. The Japanese nationals were Buddhists. Among the Japanese born in Canada, many were members of the United or the Anglican Church.

Missionaries of the United Church were teachers in the high school, while missionaries of the Anglican Church taught kindergarten. READ MORE

Tashme Voices

Once I attended a cremation for the daughter of a family friend. The site was a forest clearing. The coffin was placed on a funeral pyre, then lit. We kept an all-night vigil, speaking quietly and listening to the gentle breezes waft through the firs and pines. At dawn, we left. The family members came to collect bone fragments and ashes. There were no cemeteries in Tashme. – Victor Kadonaga

Tashme Voices

Right after we got to Vancouver, my husband started to agitate, saying he wanted to do some work that would help the government. He got the idea of mending shoes in a camp. There'd be hundreds of people, children included, so any number of shoes would get worn down. It happened that a man he'd done favours for in Prince Rupert was a shoemaker, and he was regarded as dangerous, so he got interned and put into a special camp for enemy aliens. My husband took over all the machinery and tools the man owned, and applied to the Commission for shoe repair work. They approved, and that's how my husband went to Tashme, where the biggest camp was, and became a shoemaker. He got everything together in Vancouver, the machinery and the materials, before going to Tashme. He was lucky. He couldn't do shoe repairs, as he didn't know how, so he got some experienced men to do the work and made himself the boss. The rates for repairs were low, so everybody in the camp was happy; he was doing something for them. The Commission people trusted him, too, and they treated us well. So when we left Tashme, they told him he could take all the materials left over from the sewing machines, for free. He sent it all to Toronto as five tons of freight. At the time, he learned by observing, and got to learn shoe repair somehow or another, and thanks to that, when we resettled in Toronto, he carried on as a shoemaker for six years. In Tashme, my husband worked as a shoemaker, I was a mid-wife, and our daughter taught school. We all got the same pay, 25 cents an hour, about 45 dollars a month. Even in the camp, people had babies. Maybe 400 or 500 Nisei were born there. There were about 4,000 Japanese in Tashme, so we had every- thing: schools, a hospital, bathhouses and a shoe repair place. The two of us midwives took turns working day or night shifts, and we were very busy. My husband was the boss of the shoe repair shop, and he didn't do anything, just counter work, so he could take it easy. He organized a baseball team and for three whole years he was the manager. He worked all right, but he liked to have fun, too. – Mrs. Yasu Ishikawa

from Picture brides: Japanese women in Canada by Tomoko Makabe

Page header: NNM 2013-58-1