The forced removal abruptly interrupted the schooling of Japanese students. Although the education of all children in Canada was a provincial mandate, the government of British Columbia argued that the education of Japanese Canadian children was no longer its responsibility because the relocation was a federal mandate. During the period of relocation and dispersal, no provincially qualified teachers were available to teach the interned students. The Department of Education refused to hire teachers for a short period of time. In the fall of 1942, it looked as if Japanese children would not be educated.

During this period of uncertainty, parents and volunteers took matters into their own hands and set up an emergency school in Hastings Park and in church facilities in Vancouver. Miss Hide Hyodo, a 16-year veteran of the BC school system, and her co-director, Miss Chitose Uchida, took on the challenge of providing education to the children in Hastings Park and later throughout the camps. They trained high school graduates who were willing to become teachers in the camps.

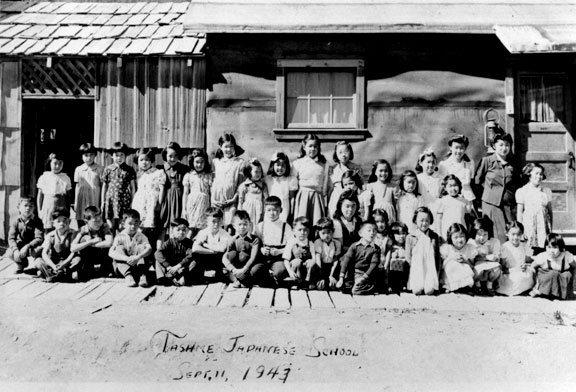

Eventually, after Japanese Canadians arrived in the internment camps, the BCSC accepted responsibility for providing education only for elementary students in grades 1 through 8. In most camps, church missionaries provided high school education and kindergarten care. In Tashme, the United Church missionaries were well loved and appreciated for their assistance in education and many other duties.

Thanks to the teaching staff’s hard work, students in Tashme received a quality education. The schooling proved so successful that many students easily integrated back into local school systems following internment. In Tashme they were given the tools to reach academic success and ultimately to live successful lives.

In September 1942, the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Council set up an emergency school for Japanese children of Vancouver who were refused registration at public schools because of the evacuation order. The local school boards took the position that it would not accept students for the few weeks or months until students were evacuated. This emergency school accepted registrants on a volunteer basis and operated from the Powell Street United Church hall. The school operated until the students were evacuated. Directors were Miss Hide Hyodo and Miss C. Uchida. From New Canadian 1942-09-12-01

BC Security Commission today told The New Canadian that correspondence courses would be provided, but that financial limitations will necessitate that volunteer teachers' assume the work of coaching and instructing. The provincial government at Victoria insists that it is without either moral or financial responsibility, and has refused to "contribute in any manner, shape, or form" toward the education of the children evacuated from the Pacific Coast. The Security Commission itself will therefore provide at its own expense correspondence courses, necessary text-books and a minimum of supplies. Supervisors in each of the projects will co-operate in making available whatever quarters they can, so that the school children can gather to follow their, studies by mail. In addition a small number of Nisei “school secretaries" will be employed by the Commission to carry cut the work involved in receiving and distributing the courses, legislation and classifying of pupils, arrangement of quarters, filing and care of "text and reference material.” From New Canadian Oct 10, 1942.

Organizing Education

The Hastings Park school project begun by Miss Hyodo became a model for establishing schools during autumn 1942. Once the BCSC was in charge of providing elementary education in the camps, it drew from the Hastings Park system when developing schools in the Interior, with assistance from early leaders like Miss Hyodo. She helped to organize an infrastructure for internment camp schools and set a precedent for other young Nisei to be hired as teachers in the camps.

The newly-established camp worked in cooperation with the BCSC throughout the late months of 1942 and beginning of 1943 to set up schools. In Tashme, because of the challenges of setting up classrooms in farm buildings, hiring teachers, and acquiring school supplies; students did not start attending classes until January 26, 1943. By that time, most students had fallen behind nearly a year in their studies, and 600 children showed up for classes. On that first day, workers needed to finish installing heating equipment so the school was too cold to attend and children were sent home.

Hiroshi Okuda was appointed as the first principal at Tashme’s elementary school. A graduate of the University of British Columbia, he first volunteered as a math teacher for the temporary high school that had been set up at Hastings Park. Mr. Okuda continued on to Tashme, where he organized and recruited teachers. As principal, Mr. Okuda was in charge of approximately 600 children. He successfully overcame difficulties in creating a school, setting up classrooms, and acquiring textbooks and supplies.

A parents’ association was formed, headed by Masakaru Morigatsu, and petitioned the BCSC for continued improvements in education. The association not only worked to help administration in the school, but also raised money from parents in order to pay for textbooks.

BCSC Annual Education Reports

1942 BCSC Annual Report on Education

1943 BCSC Annual Report on Education (January to June)

1943 BCSC Annual Report on Education (September to October)

1944 BCSC Annual Report on Education

1944 BCSC Annual Report on Education

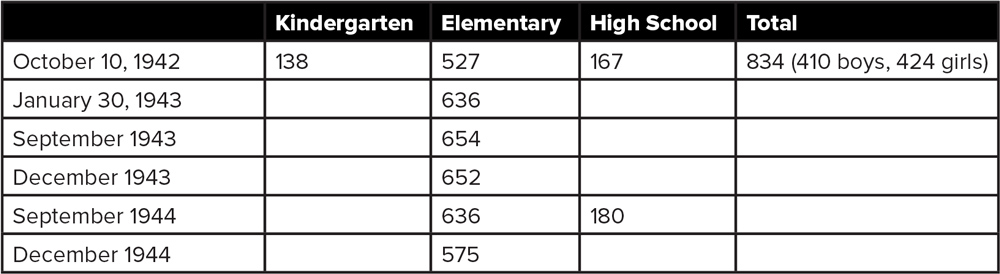

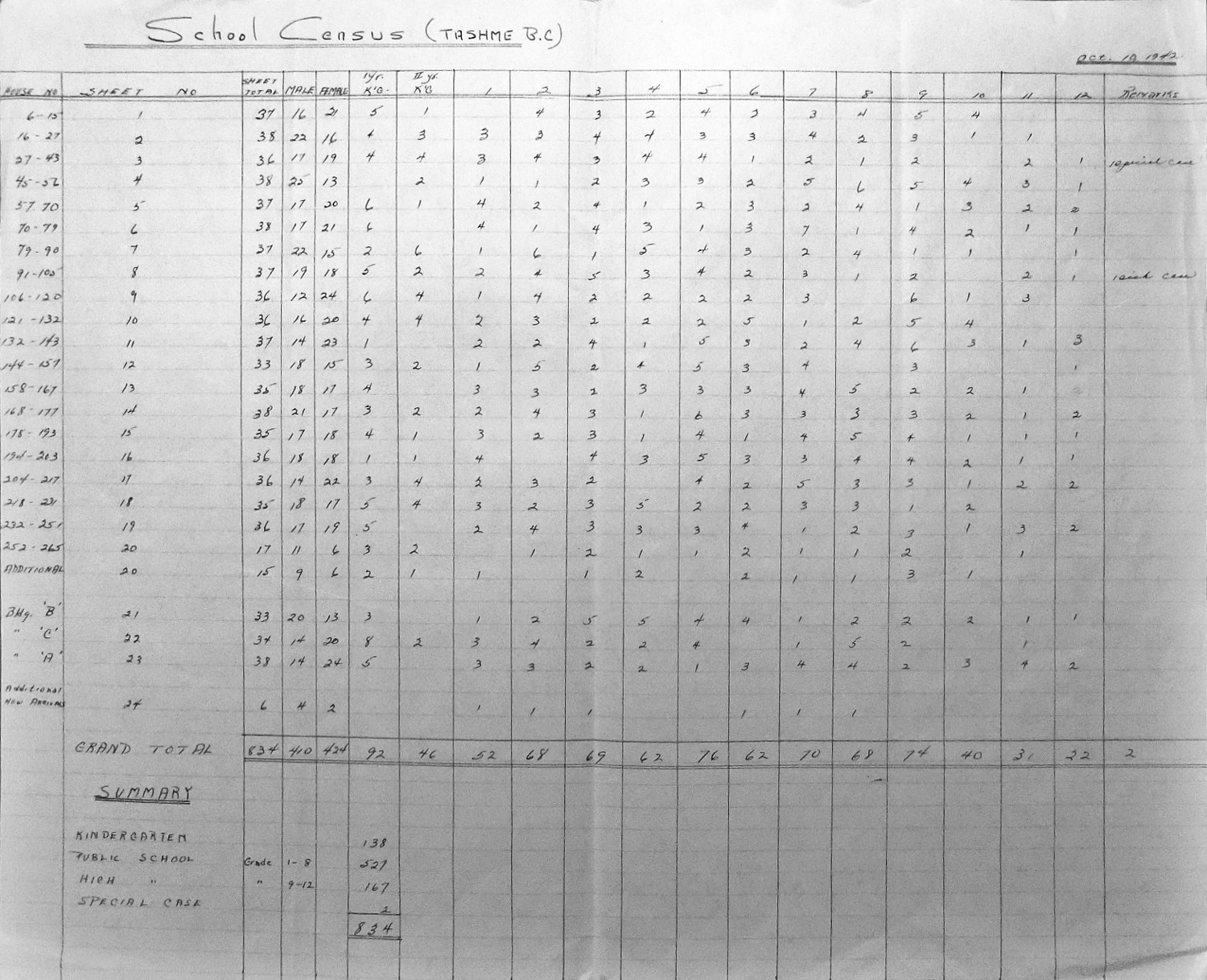

This chart shows the number of students enrolled at different grade levels in 1942, 1943, and 1944. After 1945, the numbers of students fell off as families moved out of Tashme, many to eastern Canada.

Kindergarten

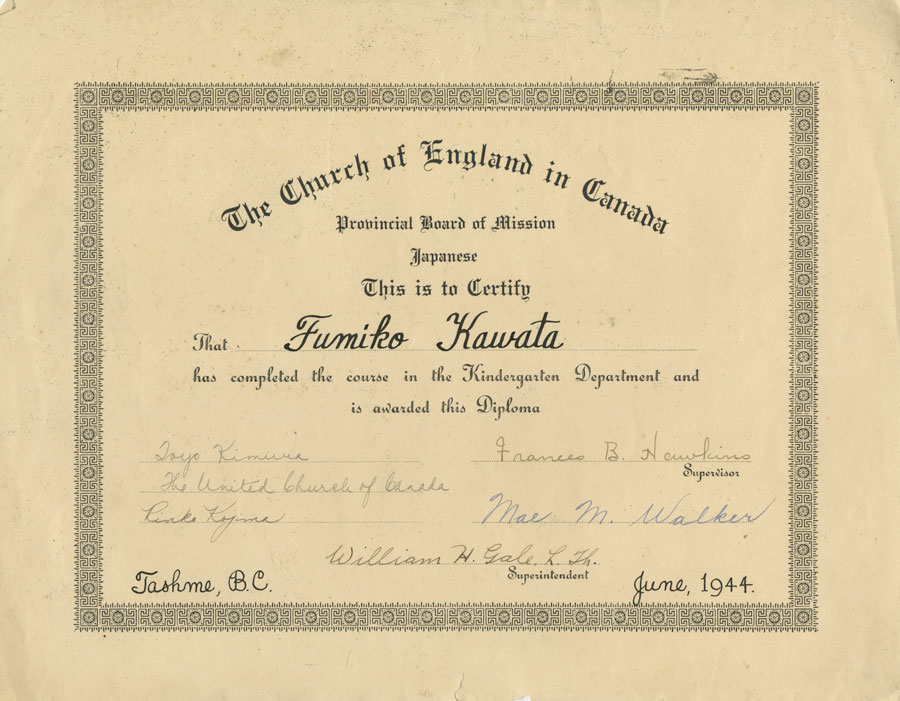

Kindergarten, which might better be described as daycare, was operated and administered by the Anglican Church. Anglican missionaries Miss Hawkins and Miss Walker, assisted by two Japanese girls, taught kindergarten classes to about 120 children. Two classes were conducted, one in the morning and one in the afternoon, between 9:30 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. in a separate building located in a grove of trees that served as both a kindergarten and the Anglican Church. Kindergarten allowed young children to participate in an educational and social program. It also provided an opportunity for interested parents to take classes in English.

Elementary school

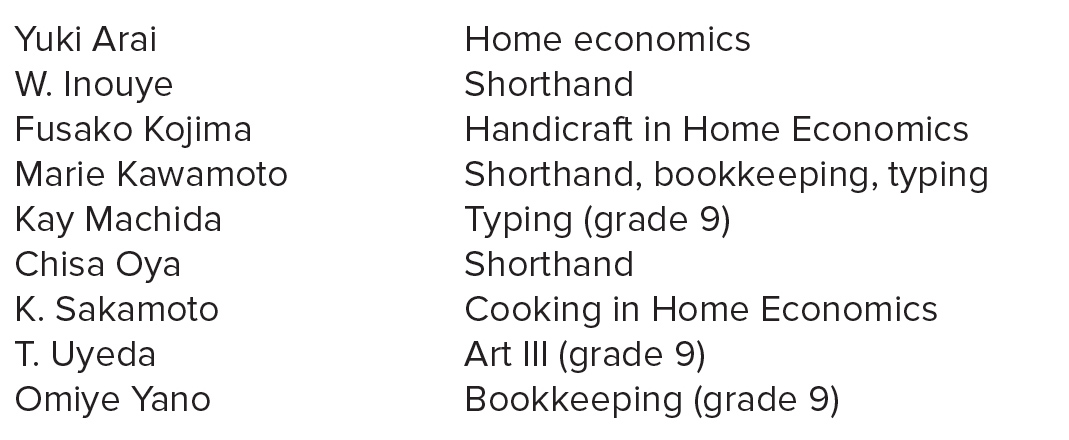

When the elementary school opened in January 1943, it was staffed by 30 teachers, many of whom had never taught before moving to the camp. Most were Japanese Canadian high school and university graduates who simply volunteered to help out in the elementary classrooms, and they helped teach non-academic courses. The early weeks were very difficult as many teachers were unfamiliar with the curriculum. Gradually they gained confidence. Ad hoc teacher training was augmented by several weeks of formal teacher training during the summers of 1943 and 1944.

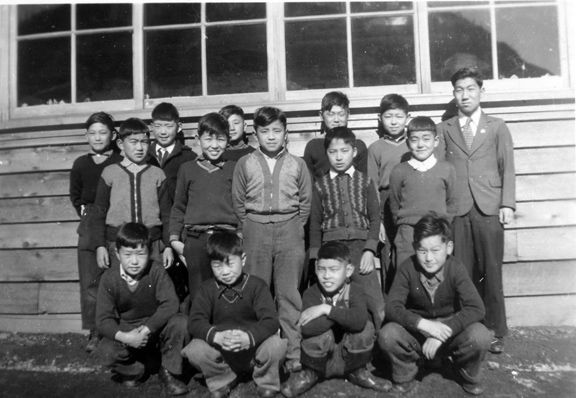

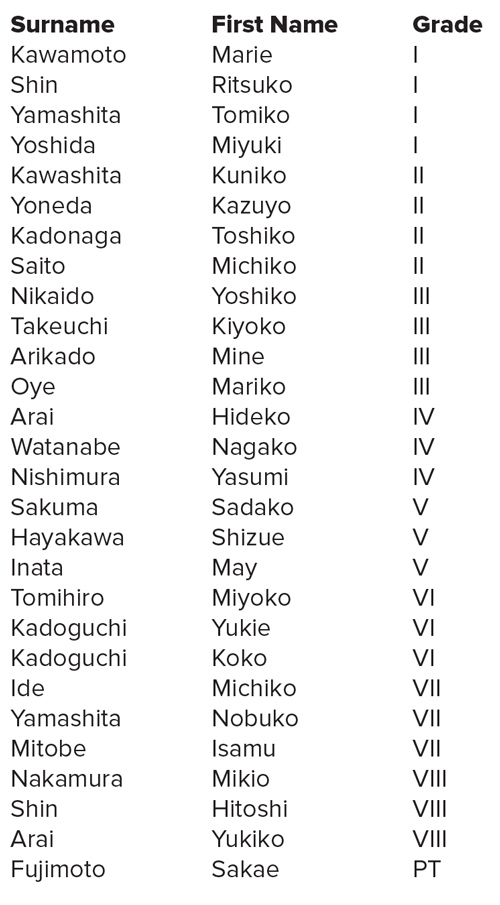

The following were the elementary school teachers as of May 1943.

High School

In each school year there were over 150 high-school-aged students in Tashme. Although the parents' association petitioned the BCSC to establish a high school, the BCSC not only refused to build the school, but also declined the parents’ proposal to pay for and build it themselves. In response, the parents reached out to the United Church of Canada, which had already supported their children’s education in Hastings Park.

A United Church minister, Reverend Wilbert Roy McWilliams, "Mr. Mac" to many, played a pivotal role in setting up the high school, recruiting teachers and ultimately providing the education that both the provincial and federal governments denied. Winnifred Awmack, a teacher, wrote about how the parents approached Rev. McWilliams to ask: "Can the church do something? Our children need high school or they will always be labourers." Rev. McWilliams immediately went to work, consulting with the church, recruiting teachers (including May McLachlan, a teacher who had returned from Japan on the exchange ship MV Gripsholm), and negotiating for classroom space and school supplies. Miss McLachlan and Douglas Saunders of the BCSC Welfare Department founded the high school.

The Women’s Missionary Society (WMS), under the United Church of Canada, ultimately organized the high school, arranging for the students to take provincial correspondence courses. Students were required to pay $9 for each course, in addition to the base fee of $2, as they were considered “aliens.” This was an extremely steep price for parents who had just lost their sources of income and been relocated with little warning. The BCSC, however, chose to cover the $11 enrolment fees and purchased basic textbooks.

Through a great feat of collaboration between various members of the community, the correspondence high school was successfully launched. Students shared the limited number of textbooks provided through the BCSC, and teachers volunteered their evenings despite the lack of compensation. Students in turn took responsibility for janitorial work and maintenance, and a couple of young Nisei women were employed as secretaries to distribute the courses, classify the pupils, and perform other administrative duties.

It wasn’t much, but the set-up succeeded in helping students to continue with their high school education and keep up with the provincial standard. The correspondence classes for high school students were arguably the most important educational feat accomplished in Tashme. With the help of their teachers, the students studied English Literature, Grammar, Social Studies, Health, Mathematics, Science, Latin, French, and Chemistry. Young Nisei teachers also taught non-academic electives, such as mechanical drawing, home economics, handicrafts, shorthand, and business classes.

Organized Japanese language instruction was restricted by order-in-council throughout the internment. Some parents taught their children Japanese on their own or at each other’s homes while the RCMP looked the other way.

In spite of the financial and space limitations that the high school students and their teachers faced, there was a strong sense of community within the school. At the start of the second school year the students became organized, with a school song and student council that planned non-academic activities. The central location of the school in the same building as the community hall further cemented the role that school played in the social lives of the young members of the community.

158 NISEI TEACHERS PREPARE FOR CLASSES AT END OF SUMMER SCHOOL - Importance of Teaching Position Stressed by A. R. Lord in Final Talk

NEW DENVER Completing a strenuous four weeks course of study in basic teaching methods, 158 Nisei teachers left for their various centres to begin a new term in the BCSC schools. From their studies they took with them pointers and new ideas imparted to them from the instructions from the Vancouver schools. Certificates will be mailed to them as soon as they are ready, Hide Hyodo, school director, stated. From New Canadian 1943-08-28

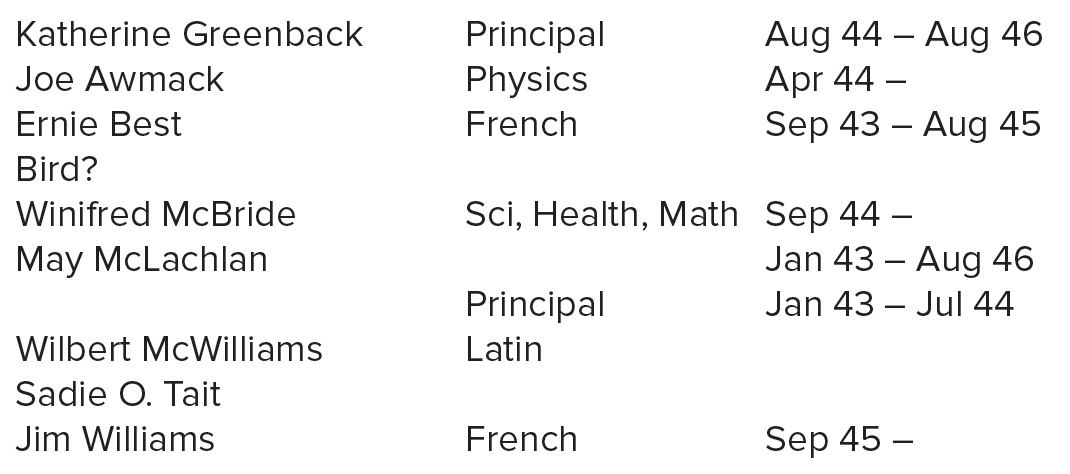

High School Teachers

Many high school teachers were recruited through the United Church. They were Caucasian Canadian university graduates who came from a wide variety of backgrounds. Notably, May McLachlan and Katherine Greenbank had both lived and taught in Japan before coming to Tashme, and could speak Japanese. Winnifred Awmack (née McBride) taught science, moving to Tashme after leaving a job as chemist in a laboratory at a Vancouver fish company. Ernie Best, a Quaker and a conscientious objector who studied philosophy and history, taught until 1945 when he left to continue his studies. Jim Williams, who had affiliations with the Anglican Church, took Ernie Best’s place until the camp shut down. With a teaching staff of four to cover the academic subjects, Nisei teachers filled in the gaps.

Teruko “Terry” Hidaka’s first role in the school was teaching the recruits how to teach. Most lacked formal training and had only limited experience from helping out in Sunday schools and volunteering in the Hastings Park school project. They were assigned the less academic subjects such as shorthand, bookkeeping, typing, art, and sewing and cooking in home economics. These Nisei teachers were young women who generously involved themselves in the school community; for example, Mrs. Inouye founded the first Tashme Girl Guide Company, and Miss Yano played piano for the United Church Sunday School.

The Nisei teachers were compensated $30 a month, their supervisors $45. The high school teachers working through the United Church earned a church salary of $75. Despite this divide, the United Church teachers lived in the same conditions as their co-workers and pupils, and they continued to receive thanks for their contributions to the school and community for decades after Tashme shut down.

The high school academic teachers were:

The Nisei teachers who taught non-academic high school courses were:

The Nisei teachers benefited from intensive summer teaching training courses that took place in New Denver during summers of 1943 and 1944, provided by teachers at the Vancouver Normal School. This training gave the novice teachers tools to succeed in the coming year. The courses were intense but there were many social events to ease the tension and develop a strong sense of commitment and responsibility.

Teaching Experiences in Tashme

To the left side of the entrance to my classroom, I placed my new small high desk with open shelf, and my tall stool. The old blackboard hanging on a partition close to my desk designated the front of the room. For the pupils, there were well-worn two-seater desk sets much like the ones we used in the Japanese language school in Kitsilano. The classroom furniture had been shipped in to camp schools from the coast by the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property.

At 9 a.m. that first day, a big brass bell was rung by hand, and all the children gathered at their pre-arranged entrances. Orderly lines were formed. My class was at the side entrance to D Building, and we filed into our room without incident.

After the blanket was pulled down in the doorway, and we were thus isolated from the other classes, the first day began. I lettered my name, "Miss Hayakawa," on the blackboard, turned to say, ”Good morning, class," and the answer came back, "Good morning, Miss Hayakawa." READ MORE

Tashme Voices

Becoming instant teachers was no easy task; my own first assignment was first graders whom I later realized were more difficult than third and fourth graders. Lacking materials, each evening meant stacks of homework to prepare for the next day’s lessons: colored pictures were drawn on rough newsprint, lessons drawn with a purple pencil onto gelatin pads and hand-rolled onto paper. After printing several pages, items would be hardly visible. Throughout those years with the school, I taught all elementary grades and also assisted high school students with correspondence courses in the evenings. This latter task was initiated with the help from the missionary teachers.

When the B.C. Commission recognized our classes as a regular school, we saw a vast improvement as complete sets of regular textbooks and teaching materials became available. During each summer holiday season all the teachers from the many other camps and areas gathered in New Denver for teachers’ training courses with the assistance of instructors from the Vancouver Normal School. – Marie Katsuno

Tashme Teachers

May McLachlan was a teacher and principal at the Tashme high school. She was one of two, the other was Katherine Greenbank, who were in Japan at the start of the war, and returned to Canada in August 1942 as part of the exchange of persons held in detention in Japan during the war. READ MORE

Classrooms and Resources

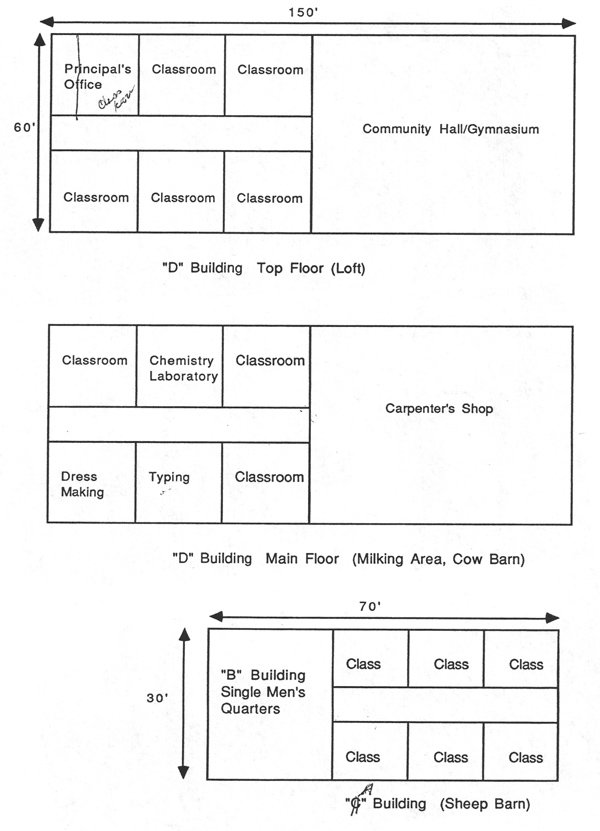

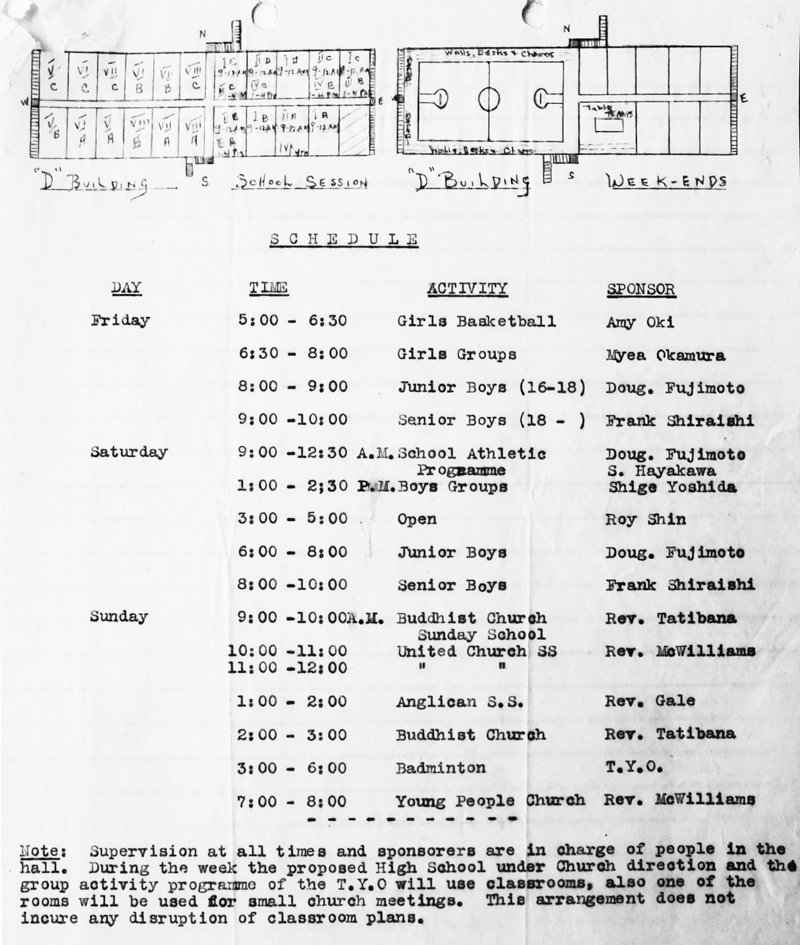

There was no building specifically designated for school. The upper floor of the D building, formerly a cow barn, was the main school location. This space was partitioned into 25-by-25-foot (7.6-by-7.6-metre) classrooms with the help of 10-foot-tall (3-metre-tall) partitions. Each partitioned classroom held an average of 17 students. The only permanent room served three roles: principal’s office, staff room, and supply closet. Classes were held from 9:30 a.m. until 9:30 p.m. every Monday to Thursday, and from 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. on Friday. The noise level of simultaneous classes was a constant problem.

On weekends, partitions in half of the upper floor were removed to create a community hall or gymnasium, used for community events, since this was one of the biggest open indoor spaces in Tashme.

The A building, formerly a sheep barn, was also partitioned into classrooms. Although smaller, at about 15 by 15 feet (4.6 by 4.6 metres), they provided a space for grade 8 students to study. The partitions were removed to accommodate smaller community events, meetings, and church services, including weddings.

Elementary school took place during regular school hours, from Monday to Friday. Because of the lack of funding, high school classes, using the same facilities, followed from 3:30 to 5:30 and 6:30 to 8:50. Many high school students attended their classes after a day of working in the store, office, hospital, blacksmith shop, and other places during the day. For those who worked very late, teachers would stay past 9:30 to assure that they kept up with the required curriculum.

For the school year 1944-45 and later, an additional elementary school was established by remodeling an existing woodshed into eight classrooms for the early grades.

The lack of funding for schools in the internment camps meant that students had to make do with limited supplies. Principal Okuda brought desks from Vancouver. Two students sat to a bench, sharing the limited 12-by-36-inch (30-by-91-cm) workspace. Textbooks were in short supply, and there were insufficient resources for purchasing new books. In some cases, textbooks brought from home were shared among students in the same grade. To solve this difficulty for high school students who were preparing for provincial examinations, the United Church provided the funding to purchase each student a worksheet booklet, a necessity because of the limited number of teachers. Eventually the parents’ association raised funds from parents to purchase additional texts.

Tashme’s makeshift high school classrooms did not have the same supplies that were available in public schools. The classes were based on correspondence courses designed for homeschooled students, and so for classes like chemistry or biology that required a laboratory component, students made use of household products. Ms. Awmack wrote in her memoir about arranging with her old employer to send a variety of fish to Tashme so that students could study them for biology. When they were done, students could take the fish home to be cooked for dinner. Additionally, the high school teachers were given more liberty in curriculum creation, and thus the students were not as reliant on textbooks as their public school counterparts.

School Activities

Weekends were filled with school-related activities that enriched young people’s lives although they didn’t contribute directly to their graduation requirements. There were periods for worship and socializing. A regular Saturday feature was Music Appreciation. The classroom partitions were taken down, and everyone gathered in the hall to listen to classical records played on one of the only record players in Tashme. The first half of Music Appreciation focused on classical music and its history. A teacher would explain the highlights and history of a record before everyone in the hall listened to it together. Two classical records would be discussed at each session. Following this, teachers allowed students to play popular records. Ms. Awmack wrote about teaching students to dance to these records, and recalls how some of her former students went dancing together years after their time at Tashme.

Sunday school was also popular among the youth. Read more about religion in Tashme. It is important to note that all of the teachers recruited for the high school were religiously affiliated, with either the Anglican or United Church, and this affected the way education functioned in Tashme.

Extra-curricular activities manifested in many ways that spilled over into daily life in Tashme. Sports teams, dances, outings, Boy Scouts and even work were connected to school life. High school students formed social groups such as the Tashme Youth Organization (TYO). See Clubs 4.6 Many high school students worked during the day and attended class at night. If their work went late, teachers would push class to a later time to assure students were up to date on their schoolwork. The youth in Tashme took on responsibility for arranging many of the social events that took placed in the community, such as a Sadie Hawkins Dance. The active lives that these students led are most clearly evident in the school annuals they started making in the 1943 school year. Different grades made their own annuals, with pieces reflecting on their experiences in the camp. They provide a window into the life that the Tashme school provided to a generation of young people living in the Camps.

The Tashme High School provided students with more than extra-curricular activities and a connection to the world outside of the camp. Thanks to the teaching staff’s hard work, students in Tashme received a quality education. In fact, the school system proved successful in that the students were able to easily integrate back into local school systems following internment. In Tashme they were given the tools to reach academic success and ultimately to successful lives.

Despite deprivations, Tashme high school was an important part of the community because of what took place outside of the classroom. The young Nisei who attended the school were given the opportunity to participate in a wealth of school affiliated activities that encouraged and motivated them to be productive.

TASHME HIGH ANNUAL WINS MENTION

Receiving favorable comment in a review of BC high school annuals entered in the competition of the Province Shield awarded to the best high school annuals was the Tashme Lycee, published by the Tashme Correspondence School under editor James Shino. The shield is awarded annually by the Vancouver Daily Province. The commentary declared: “Large literary section reflects the thoughtful attitude of students who study correspondence courses at night, under teachers’ guidance. Candid shots an improvement over last year. Brief features on incidents of school life well handled and personals good.” From New Canadian 1945-10-08-08

Related Excerpts

Teaching in Canadian Exile

When the ghost town schools opened in 1942 or 1943 the original teachers were without any formal teacher training. Some fell back on related experiences in their former communities, such as teaching Sunday School or running Canadian Girls in Training (CGIT) groups. And a handful of the camp teachers got their first hand experience of teaching classes of wholly Nisei children at the Hastings Park holding centre during the spring and summer of 1942. READ MORE . . .

Educating Japanese Internees During WWII: Tashme High School

Once the Japanese had been labeled “Enemy Aliens”, they were subject to the War Measures Act, and became the responsibility of the federal government. Consequently, the provincial government refused to provide education for the Japanese children. The federal government only supplied teachers and course materials for grades 1 to 8. It was not until January 1943 when the Women’s Missionary Society (WMS) of the United Church organized and operated a high school that education became available for Japanese secondary students. READ MORE . . .

The Presence of a Past Community: Tashme British Columbia

The planning of educational facilities at Tashme, by the authorities, was apparently ineffective at first. That is, the constitutional frameworks for education were being debated between Provincial and Dominion levels of authority. To the internees, the indecision was distressing. The delays in decision making combined with inadequate facilities, made the first school year at Tashme (1942-43) the most difficult year for both staff and students. READ MORE . . .