Tashme 101

Tashme-at-a-glance

Opening date: September 8, 1942.

Closing date: August 12, 1946.

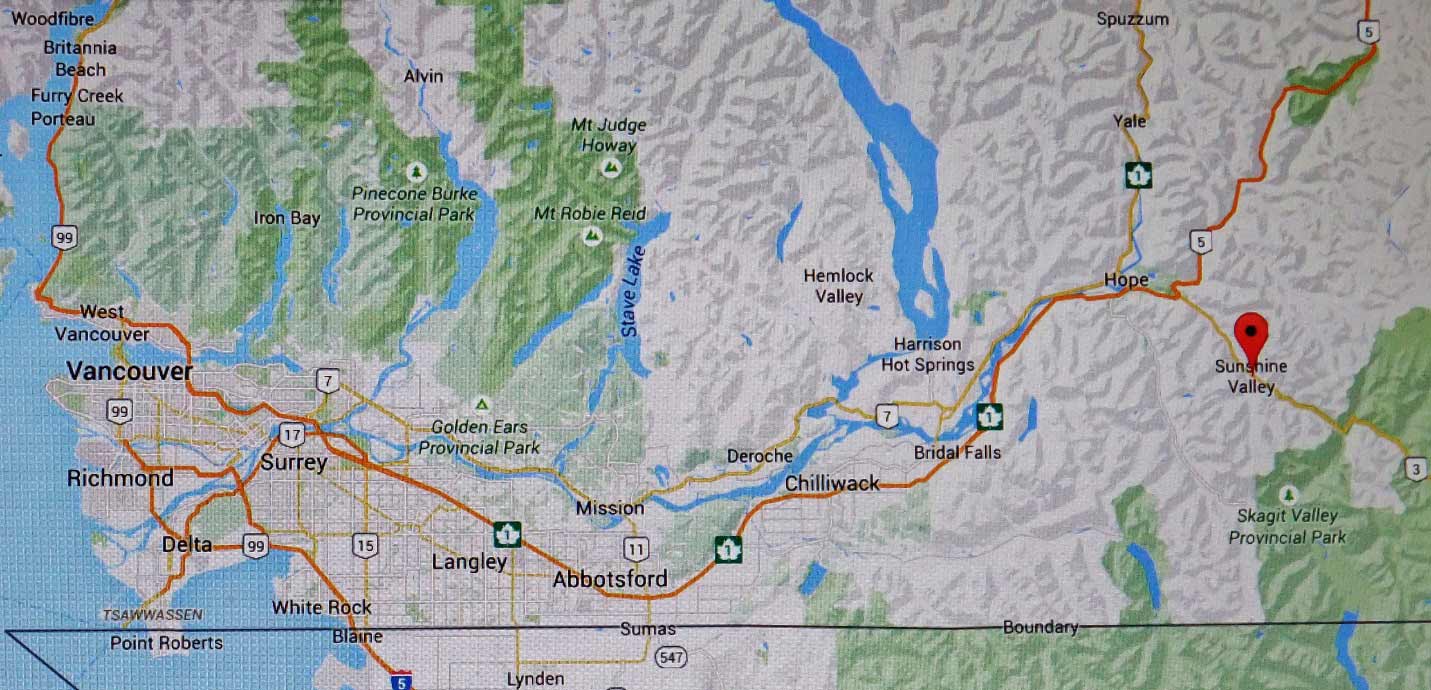

Location: 14 miles (22.5 km) southeast of the town of Hope, BC, in a valley about one mile (1.6 km) wide and four miles (6.4 km) long, along the old Royal Engineer’s Road that would eventually become part of the Hope-Princeton Highway.

Site: Fourteen Mile Ranch, a 1,200-acre (456-ha) dairy and livestock farm leased from Amos Bliss Trites, a successful mining executive.

Elevation: About 2,300 feet (700 metres) above sea level.

Temperature range: From a high of 35 degrees C in summer to a low of -20 degrees C in winter. Weather chart.

Population:

• Planned population: up to 2,966 persons.

• Peak population: 2,644 residents, as of January 6, 1943.

• Staff: about 40 Caucasians, including BCSC staff, the RCMP, hospital and other government employees, and about 9 missionaries.

In Brief

A small town was constructed from the original farm buildings and the building of 347 primitive wooden tar paper covered houses, schools, a hospital, a power plant, RCMP detachment, fire hall, churches and a commercial center.

Tashme was administered initially by the BC Security Commission and later by the Department of Labour of the Government of Canada and the Shinwa-kai, a committee formed by the Japanese residents.

Because of its isolation, Tashme was a self-sufficient community with its own governance, commerce, schools, churches and local economy.

The activities of everyday life were limited but the resourcefulness of Tashme’s residents made the dreary life bearable.

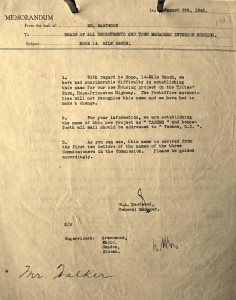

What’s in a name?

What’s in a name?

The property was originally called “Hope 14 Mile Ranch BC,” but Canada Post would not recognize that name. TASHME was created by taking the first two letters of the last names of three BC Security Commission officers:

- Austin T. Taylor, a prominent Vancouver businessman

- John Shirras of the BC Provincial Police

- Frederick John Mead of the RCMP

A Brief History

Japanese people began to immigrate to Canada in 1877, when Manzo Nagano became the first Japanese to land and settle in Canada. From the beginning, the rights of the Japanese and other Asian immigrants who followed were restricted. See www.japanesecanadianhistory.net.

The history of Tashme, and of all the Canadian internment camps, began on December 7, 1941, the day that Japan attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Immediately, Japan declared war on the U.S., Canada and Great Britain.

The Canadian government’s response was just as swift. On December 8, under the War Measures Act, Canada required all Japanese nationals and those naturalized after 1922 to register with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens. Soon, Japanese Canadians were stripped of their freedom, property and other assets.

In January 1942, the area 100 miles inland from the west coast of British Columbia was designated a “protected area.” In early February, all male “enemy aliens” between the ages of 18 and 45 were forced to leave the protected area. Most were sent to work on road camps in the BC Interior. A few weeks later, the federal Minister of Justice ordered all persons of “the Japanese race” to leave the coast. Beginning in March 1942, women, children and the elderly were sent to internment camps, many in abandoned mining or logging towns in the Interior. The British Columbia Security Commission (BCSC) was established to plan, supervise and direct this forced removal.

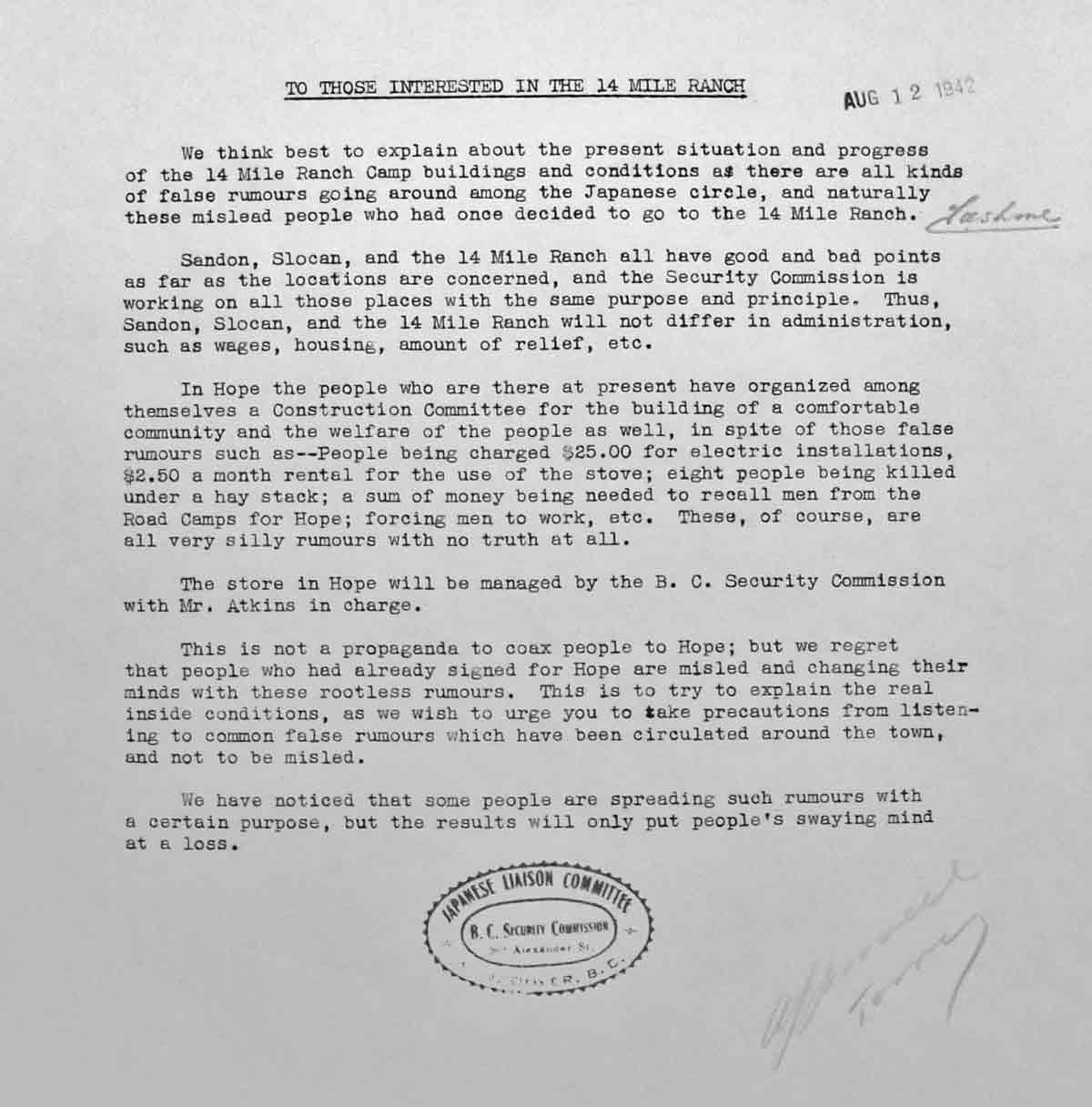

In 1942, the site that was to become Tashme was chosen to house 500 families of men between the ages of 18 and 45 who were separated from their families and sent to work on the Hope Princeton Highway while living in road camps along the route. See BC Road Camps. As the men were allowed to join their families—and because the men were needed to actually help build the camp—the need for increased housing resulted in the establishment of the Tashme internment camp.

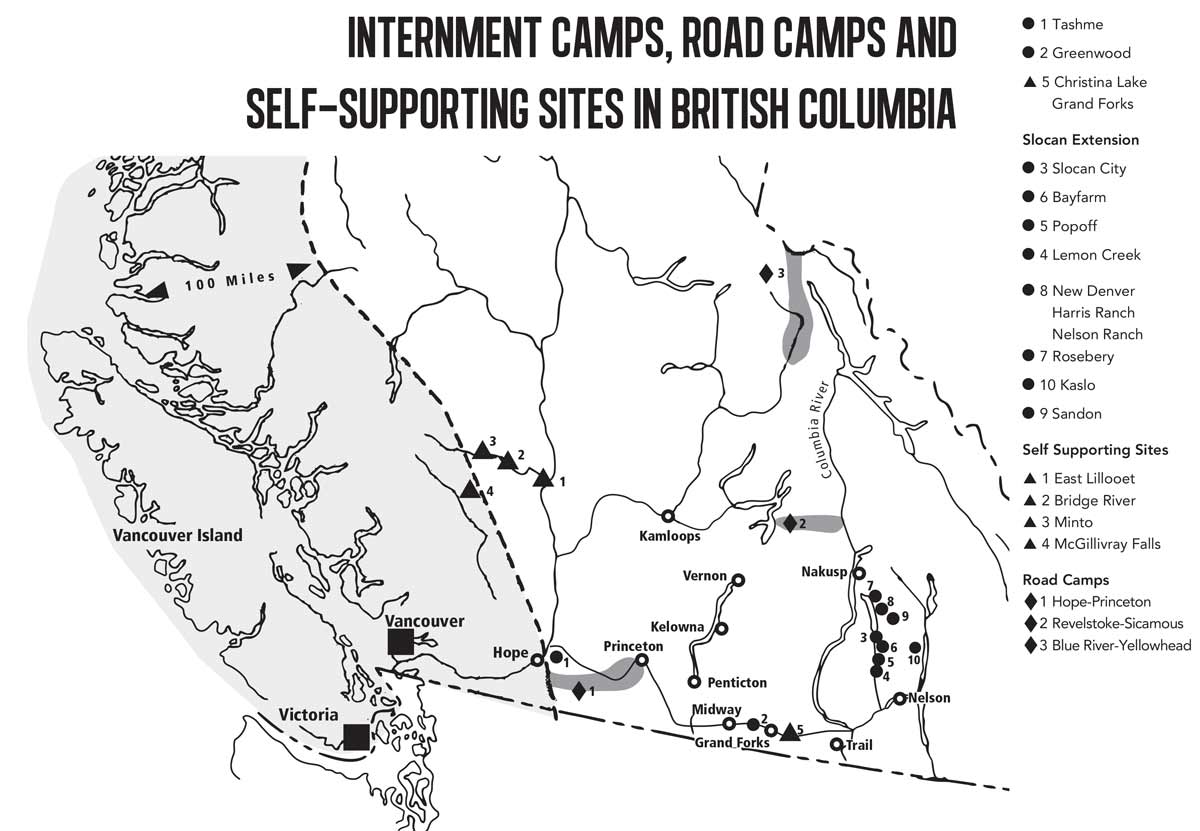

Tashme was one of ten internment camps in British Columbia. The others were:

Greenwood

Kaslo

Lemon Creek

New Denver

Rosebery

Bayfarm

Popoff

Sandon

Slocan City

Five “self-supporting camps” were located at:

Bridge River

Minto City

McGillivray Falls

East Lillooet

Christina Lake

Tashme was the last of the BC camps to be established, and the largest. It was built on a ranch located 14 miles (22.5 km) southeast of the town of Hope, just east of the 100-mile (160-km) exclusion zone

The site was a former Depression-era relief workers’ camp. The Department of National Defense leased 1,200 acres (456 ha) from Amos Bliss Trites, a successful mining executive and the owner of Fourteen Mile Ranch, for $500 per month for the duration of the war. View Lease agreement.

Tashme Voices

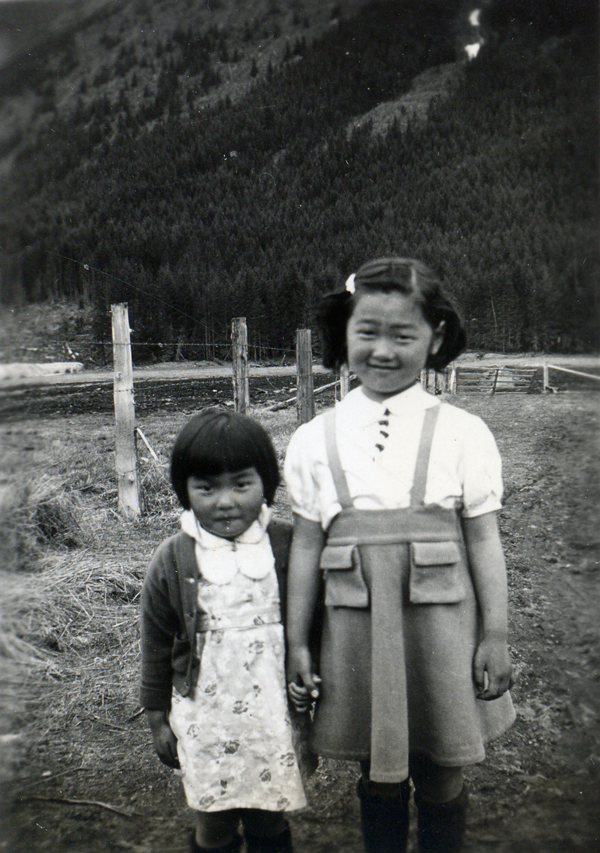

Since coming to Tashme, the feeling of bitterness and hurt, that I first felt, has gradually grown dim, and I hope by now completely erased. Being able to walk about without the diffident fear of someone looking at me with disdain, “Another dirty Jap,” has helped. Perhaps it is cowardly to be glad to flee from distrust, but I must admit that in a certain way, there is a sense of freedom even in this confined mountain hermitage, which is ours. Letters to and from our white friends, the people who love and trust us, no matter how dark a cloud hangs over us, has been a source of strength, and perhaps the greatest aid of all is the friendless and great kindness of the Church leaders, with whom we come in daily contact. This knowing the good, and only the good, has enabled me to regain the state of true poise, that was lost in the whirlpool of injustice which followed the wake of war. It is with a sense of victory that I am able, not, to read with interest, but in a detached way, the pros and cons on the question of the Japanese-Canadians. For I have come to know, no matter how prejudiced the views of some may be, there will always be the good and the kind to counteract them. – Mary Oki

The area around Tashme was sparsely populated and surrounded by the rugged Cascade Mountains. Tashme was far from the other internment camps, which were located farther east in southeastern BC, near established towns and villages and relatively close to one another. The remoteness of the site also avoided the difficulties of placing a large number of Japanese among a population of local inhabitants, difficulties experienced in the Kootenay region where the other camps were located.

Unlike the other internment camps, which were created from "ghost towns" that had once been thriving mining communities, Tashme was like an isolated company town. All of the housing, goods and services, schools, hospital, employment, and recreation were provided or operated by the BCSC or by outside religious and charitable organizations. Since there were no nearby communities, community life in Tashme was created entirely by the Japanese and Caucasian residents who were relocated there for the duration of the war.

Fourteen Mile Ranch was originally a dairy and livestock farm. Many of the original farm buildings were retained and used intact during the internment, including a horse stable, a pig barn, a slaughterhouse, a blacksmith shop and a garage. The BCSC renovated two large barns to house apartments for families, single men’s quarters, school classrooms and a community hall. Other farm buildings were renovated for use as living quarters for BCSC staff, the United Church minister and others. All other resident housing and other buildings that made up the infrastructure for the small village were constructed from the ground up.

Internees started arriving in Tashme on September 8, 1942, from Hastings Park in Vancouver. Traveling by train to Hope and by bus or truck to Tashme, they came in groups of 150 persons as houses were hastily built. Hastings Park was closed on September 28, and the last group bound for Tashme left Vancouver in early October 1942. By December 1942, some 347 houses had been built.

Accommodations in Tashme were planned for up to 2,966 persons. On January 6, 1943, the official population was 2,644. This was likely the peak population. Over time, BCSC policies changed and the government encouraged people to move to eastern Canada. Tashme’s population gradually decreased as families and individuals left to find employment elsewhere in B.C. and east of the Rockies.

In addition to the Japanese residents there were about 40 Caucasians in Tashme. These included BCSC staff, the RCMP, hospital and other government employees, and about nine missionaries. Except for these Caucasians, there were few face-to-face interactions between Tashme residents and non-Japanese persons. This isolation had profound and lasting effects on the Japanese residents of Tashme for the duration of the war and afterward.

During the four years that Tashme was open, it became a bustling small town. Residents established schools and a hospital. They devised ways to govern themselves to keep peace and order in the camp. They built bathhouses and grew gardens. There was a general store, a powerhouse, a post office and an RCMP detachment. Some people found employment in a shoyu and miso factory on the site, in logging and sawmill operations, or in the construction of the Hope-Princeton Highway. Young people participated in youth organizations and clubs. Families did their best to make life as normal as possible, despite the deprivations of internment.

Beginning in 1944, the flow of evacuees to other locations east of the Rockies steadily increased through the efforts of the Department of Labor Japanese Division to disperse the Japanese to other parts of Canada.

When the war was over in 1945, the Government of Canada extended the War Measures Act and ordered all internment camp residents, in the words of a racist slogan popular at the time, to either “go east or go home”—that is, move to locations east of the Rockies or elsewhere in BC, or “return” to Japan. By June 1946, groups were leaving Tashme every week for locations east of Rockies. Most of the residents remaining in Tashme were destined for repatriation to Japan. Tashme became one of the camps, along with Lemon Creek, Greenwood and Slocan, that housed people from other camps who were waiting for the departures of ships to Japan.

The Tashme hospital was closed on June 25 and its equipment was shipped to other camps. The Tashme internment camp closed on August 12, 1946. Those few remaining were left to dismantle and clean up the camp for return to its owner, A. B. Trites.

After 1946, the site was sold to Allison Lumber, a combined lumber and mining operation. For a time, it was a proposed Boys Town site. The site is now called Sunshine Valley and houses an RV park, holiday cottages and recreational facilities. The small Silvertip Ski Resort functioned in the area for a short time.

Building Community in Tashme

The building of community was a preoccupation from the beginning. While the BCSC held overall authority and responsibility for the management of Tashme, the internees established committees to organize, develop and implement policy and regulations to oversee the forced removal and the building of community operations in Tashme. A Japanese Construction Committee was elected to oversee and coordinate the formation of Tashme. This committee was replaced by the Shinwa-kai in early 1943. READ MORE

Early photos of Tashme

UBC RBSC Japanese Canadian Photograph Collection

Tashme Voices

A person's reaction to Tashme depended upon the age of that person at the time of the evacuation. Children had fun and others had their education disrupted, but for the Issei this was generally a time of sorrow. However, many learned to make the most of this confined area, which now seemed like a mini town. Baseball teams with Japanese names were formed; school and public concerts and sports meets were organized; social dances were held in the barn school (partitions were taken down to make a big hall) chaperoned by our missionary teachers (an absolute necessity as far as the Issei were concerned). May Day queen and maypole dancing prevailed, as did weddings and funerals as life went on. – Marie Katsuno

Page header: NNM 1994-69-4-27