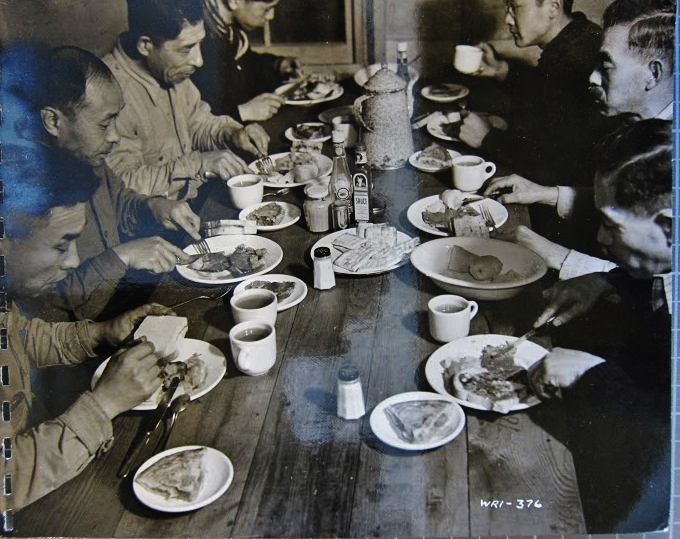

Tashme functioned as a small town, and it needed to have the services and functions that people would expect: stores, mail, newspapers, garbage collection, fire services. The residents were resourceful and creative. They used their ingenuity to create a functioning community amid difficult conditions.

Everything the community needed could be found within its boundaries. Among them, residents possessed a variety of skills such as shoe repair, barbering and hairdressing, jewelry making and repair, and professional photography including film processing. (Although cameras were banned during the internment, in most cases the RCMP looked the other way and allowed internees to keep their cameras.) Many used their spare time to renovate the interior of their homes. People found ways to keep themselves busy and to share their skills. In this way, they made Tashme a more livable community.

By mid-1943, everyday life in Tashme became somewhat routine. Construction of homes, buildings and the renovation of the pre existing farm buildings to suit the needs of the town and its residents were complete. The fields and gardens were planted and being maintained. Those who were employable found work or were assigned work, those who required financial support were cared for by BCSC through its Welfare and Maintenance office, children attended school albeit in primitive classrooms initially and life settled down into a daily routine.

Small commercial operations took root and thrived just like in any small town in Canada. In addition to the general store, there was a bakery, a butcher shop which occupied one of the original farm outbuildings, a shoe repair shop which shared a building with the RCMP, a barber shop, a hair dressing salon, and a post office. Several residents set up small operations in their homes. A jeweller who lived and worked on 9th Avenue, and Joe Seko, a commercial photographer prior to Tashme, who lived on 10th Avenue, was the town photographer and had a film processing operation in his home.

The fields and gardens produced commercial quantities of barley, oats, and vegetables like celery, cabbage, and pigs were raised for slaughter and sale at the butcher shop. However, the raising of pigs proved to be uneconomic so was closed down.

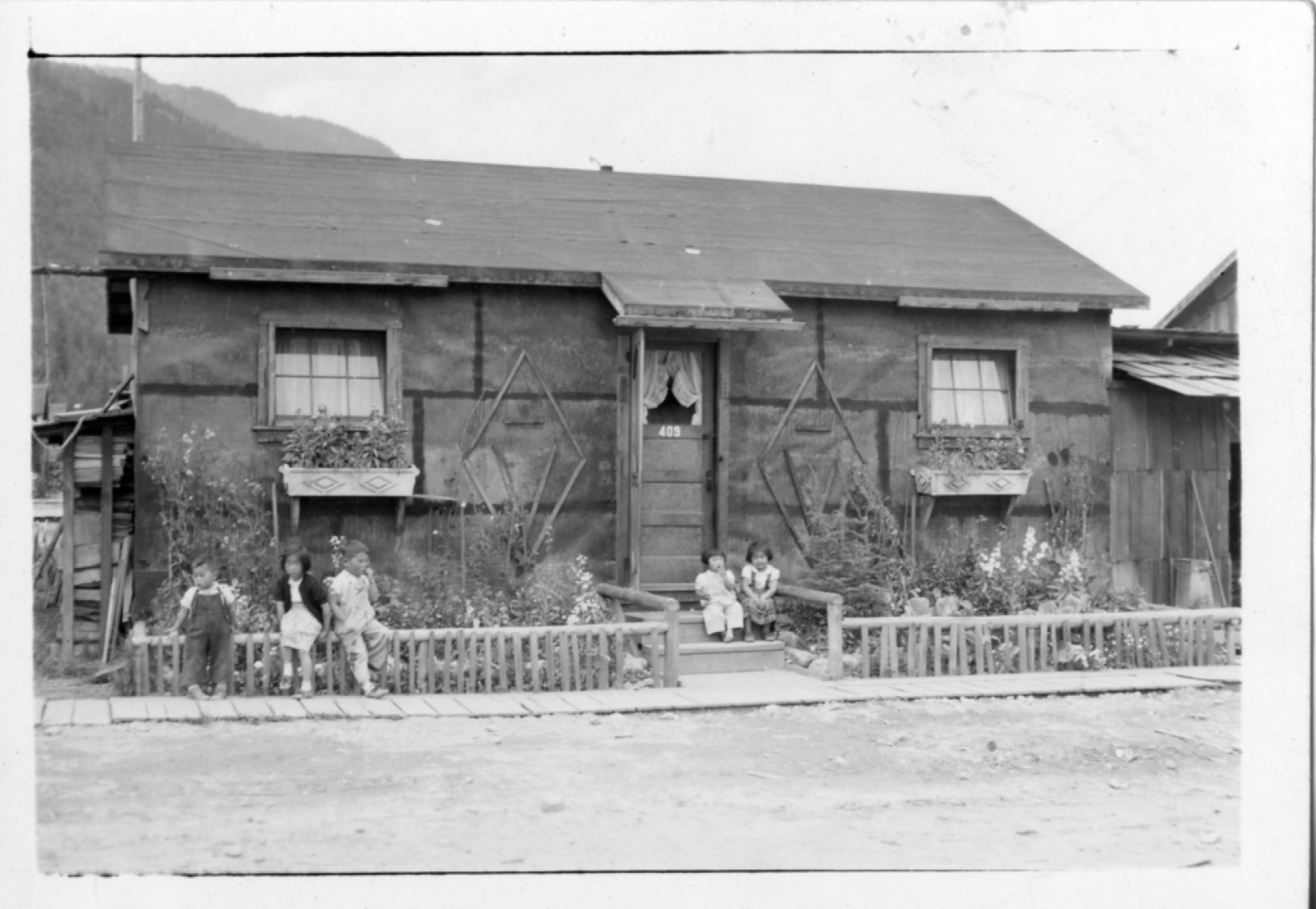

Some residents took advantage of allotment garden space and grew much of their own vegetables. Most residents developed small flower or vegetable gardens around their homes. Many also remodeled their houses with built in tables and kitchen cabinets, stools for extra seating, under bed storage and storage cabinets. Some even dug areas under their houses for additional space.

A very significant aspect of life in Tashme was centered on social organizations and social activities. Social and sports organizations sprang up and became the primary ways the young people occupied their time outside of school hours. Schools were centers of many social and recreational activities.

As in most Japanese communities of the time, the marked difference in outlook of the first generation immigrants, the Isseis and second generation Niseis, was often a source of family conflict and added to the desire of the younger generation to seek recreational outlets outside the home. As a result, the school, social and sports activities thrived since such outlets were few.

Every Day Life in Tashme – A Snapshot

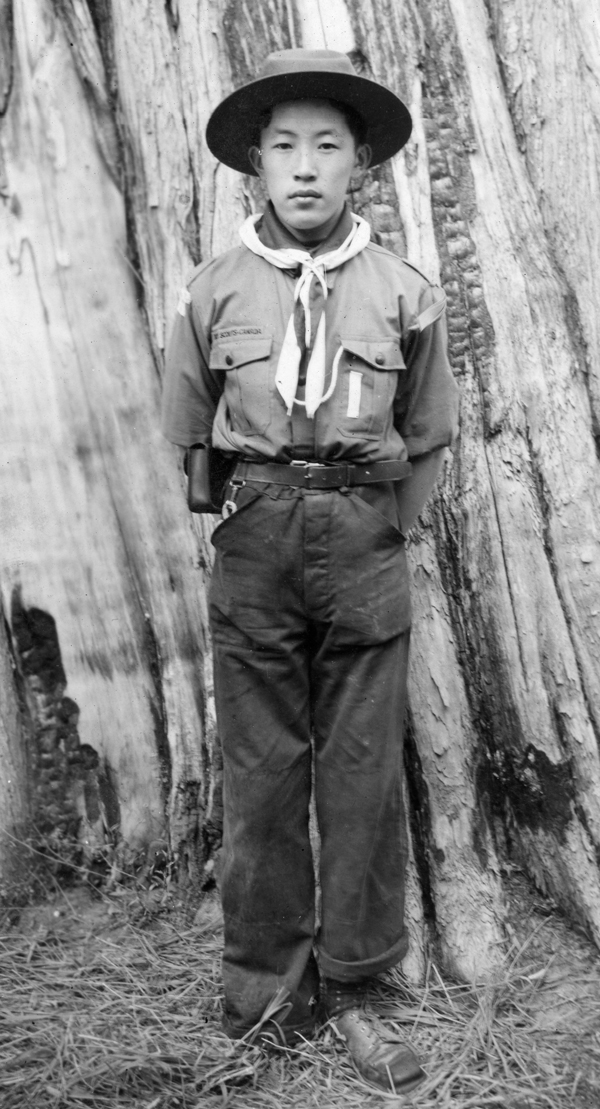

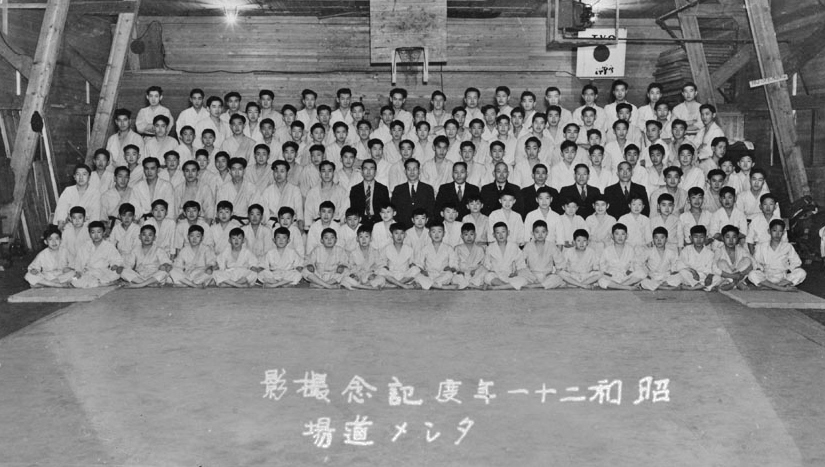

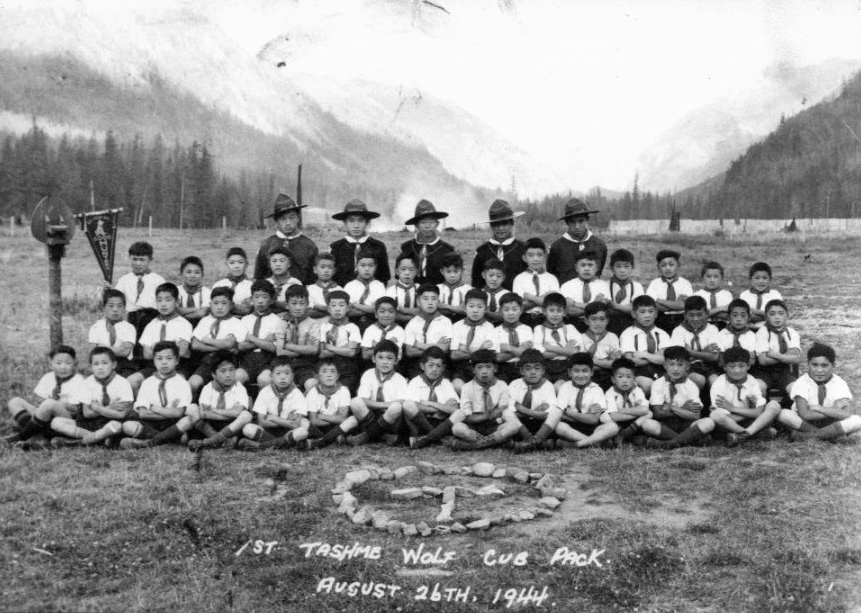

Very little has been done to improve or expand recreational facilities either for young or old during the winter months. The school hall is the sole centre for community activity, and is in great demand for shows, dances, concerts, judo, Church and Sunday Schools – both Christian and Buddhist – and athletics such as basketball. Perhaps the brightest spot in the whole picture, which Tashme can boast of over any other "ghost town" is its Boy Scout organization. Headed by Shige Yoshida, former Chemainus scoutmaster, over fifty teen-aged boys are well organized into several troops, headed by older youths. Among them are Tom Seki, Vic Kadonaga, Nobby Hori, Harvey Moritsugu, Jimmy Shino and others. READ MORE

Tashme Voices

Back in Vancouver before the war, most issei parents frowned upon dancing by us nisei lads and lassies. That had to do with the puritanical attitudes the immigrant generation had brought with them from Japan. And they were from a country where physical touching (even shaking hands) was avoided. Consequently as we nisei reached our teens, we judo students were lectured that dancing with females was not being in true Japanese spirit. Only at the local church were more western behaviour accepted: Our services were in English and we had Junior Church parties at which we even had dancing to pop-song records. But most non-church parents thought it unmannerly. – Frank Moritsugu

Shopping

All shopping transactions were conducted not with cash but with coupons. Coupon books in units of $2.50, $5.00 or $10.00, with coupons of varying denominations from one to 50 cents, were sold through the BCSC office. Purchases at the BCSC general store, the bakery, and butcher shop were made by tearing coupons out of these books. These stores stocked a limited selection of foods and goods. Since there were no other nearby communities for additional shopping options, Tashme residents had to do without or resort to catalog shopping.

Lineups frequently occurred at the BCSC stores, especially for fresh goods that were available only when deliveries arrived from Vancouver or elsewhere. Certain foods like sugar were rationed via ration books that were issued to all residents. Shopping sometimes became a complicated transaction when both coupon books and ration books were involved.

Goods not available in these shops were purchased from the Eaton’s and Simpson’s catalogs using money orders and the postal service. Catalog ordering was a primary means of acquiring clothing and other household goods. Goods were generally delivered COD via the post office.

Compare coupon shopping in Tashme with shopping without coupons in Kaslo

Municipal services

The BCSC provided all of the municipal services of a small town. A driver with a horse-drawn wagon regularly delivered wood for cooking and heating stoves.

Similarly, a BCSC employee delivered a daily ration of coal oil or kerosene for lighting. He went from house to house, filling lamps with an allocated amount of coal oil for each house. Residents were required to place their lamps on the front step every day for this delivery, since the storage of coal oil in the home was prohibited for fire safety reasons. The entire camp consumed approximately 90 gallons of coal oil per day. There was no charge for the wood or coal oil.

Drinking and washing water was available at an outside tap. Each tap served three or four houses. Water needed to be hauled to each house, usually in a pail or container, rain or shine, several times each day.

Garbage was collected from each residence once per week and taken to the town incinerator located to the east of the town.

The camp fire department was located in a specially constructed building equipped with a fire tower. From the tower, a watcher could spot fires both in the camp and in the area around it. The fire department was equipped with 2,000 feet of hose, 8 nozzles, axes and water barrels.

Tashme Voices

The silence of the morning is broken by the clop, clop, clop of a “geta,” and then the angry rush of water coming forth from the tap outside the house; somebody else has risen. Soon a thin wisp of smoke lazily rises from the chimney tops, the tangible evidence that people are awakening, one by one. The eight o’clock whistle pierces the air, a warning for the lumbermen, nurses, nurses’ aids, shoemakers, coal oil distributors and for the school children to hop out of bed.

Another day begins, the wood trucks and wagons drawn by horses rumble past the avenues; the messenger boy serenely pedals down the boulevard whistling cheerfully; the housewife hurriedly passes, to do her shopping at the Commission store. On Thursday afternoon there is a mad rush for the store, a scrambling herd, for it is then that the weekly supply of vegetables and fruits are on sale and the “line up” typical of Thursday afternoon is to be seen. Three o’clock. School is over for the day; the children stream out of “D” building (the school house), not a little red school house but a large cream colored building. They dash for the store and quickly gather in front of a window. With faces uplifted, eagerly and anxiously they ask, “is there any mail for me?” Yes, it’s the post office.

The quiet avenues are once more filled with the laughter of the children; the patter, patter, of feet going back and forth, back and forth; hockey sticks clash; girls chatter like magpies as they do shopping for mother. Some clutch milk bottles and coupons – it’s off to the dairy.

So the afternoon passes and the sun slowly begins to fall. Workmen hurry home to their warm supper, to take a dip in the “ofuro” and rest their weary limbs. Twilight approaches; the tall mountains stand gaunt in the gathering dusk; lanterns are lit in each home; a gramophone can be faintly heard. High school students trudge off to night school to tackle their correspondence papers.

Night falls and Tashme settles back to rest; thus ends another day. – Sadie Nagai

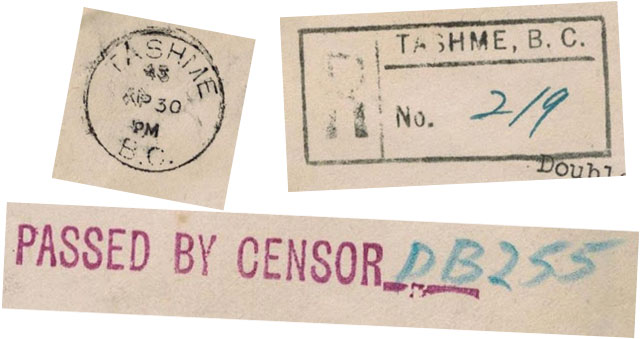

Mail

Tashme was the only internment camp that had its own post office. Because the camp was isolated, standard radio reception and telephone service was difficult and was severely limited to the authorities. Thus the postal service was the only way for residents to communicate with the outside world, to send and receive personal messages, to conduct transactions such as catalog shopping, to send and receive money using money orders, and to receive magazines, newspapers and other publications.

Censorship of personal letters was standard practice. Letters were opened and censored information was actually cut out, often making the letters, particularly those written on both sides of each page, completely illegible. Censorship was carried out locally by the RCMP detachment in Tashme.

Farms and gardens

North of the bathhouses and to the east and west of the community were areas for growing crops such as potatoes, turnip, carrots, celery, and cabbage, which were sold through the general store, and fodder (oats and barley) for horses and other farm animals. These crops were successfully grown despite the high altitude and short growing season. As well, 50-square-foot allotment gardens were provided for the residents, who grew crops for their own consumption. Many residents were active gardeners who grew flowers and vegetables on any free space around their houses or in the allotment gardens.

RECREATION

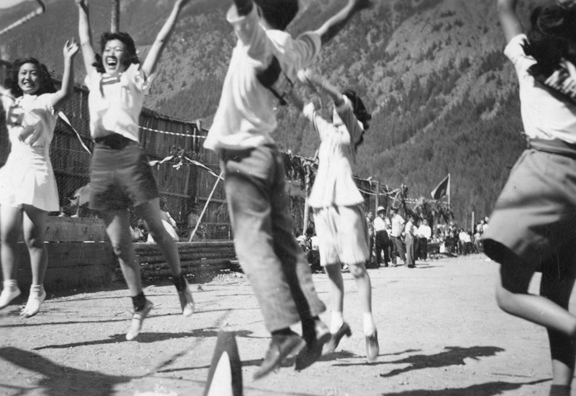

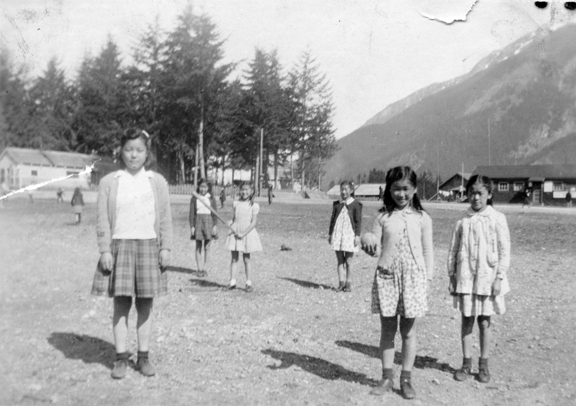

Tashme was an isolated community located in a valley surrounded by high mountains. Even in internment, however, people needed fun, and so Tashme residents made their own recreation. D building was the centre of recreational activities. A baseball diamond and sports field, located across the Sumallo River from the houses, was home to sports activities.

As in most Japanese communities of the time, the marked difference in outlook of the first generation immigrants, the Issei and second generation, the Nisei, was often a source of family conflict and added to the desire of the younger generation to seek recreational outlets outside the home. As a result, the school, social and sports activities thrived since such outlets were few.

In addition to providing education, the high school became the social focal point of the community for its students. Dances, sports, field trips, clubs and outings were largely organized through the school with the help of the teachers.

Baseball was one of the more popular sports in Tashme and the league had several teams. A student sports committee also organized ping pong, volleyball and basketball games and leagues. On Fridays and Saturdays from 3:00 to 6:00 pm, the community centre was opened to high school students for sports. In spring and fall, students participated in hiking trips, accompanied by teachers, and in winter they walked two miles west of Tashme to skate and play hockey on the frozen lake. Almost 50 boys were in the hockey league. Student organizations included public speaking, glee club, chess and checkers, current events, general science and handicrafts clubs.

Every second week old Japanese films or English “talkies” would be shown in the community centre. Many of the films were shown so many times that the children could mimic the dialogue throughout the show.

from Educating Japanese Internees During WWII: Tashme High School (1942-1946) Paul Kirschmann, March 3, 1992

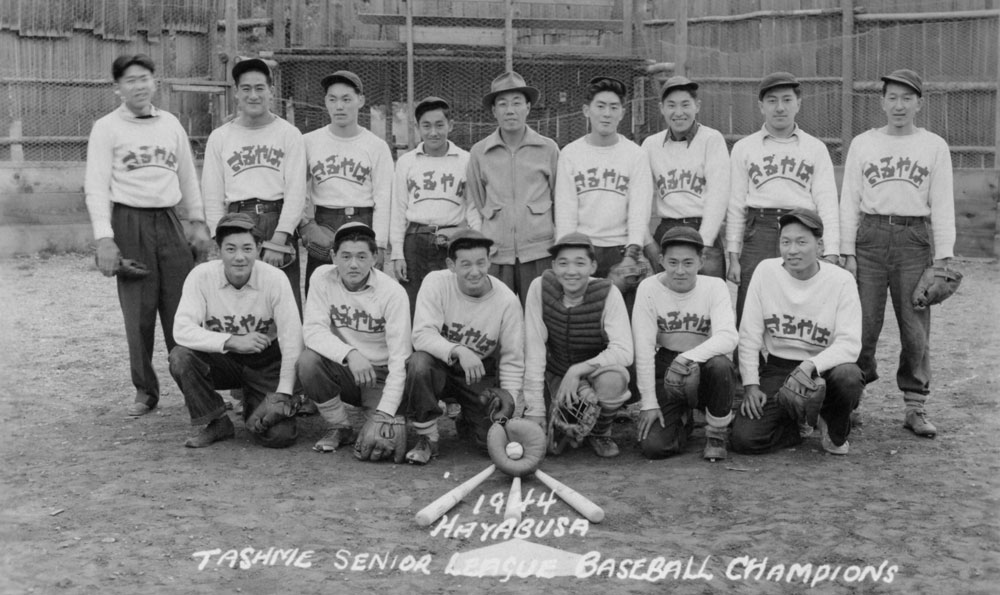

SPORTS

Baseball, basketball, hockey and judo were played and practiced at Tashme.

Baseball

In 1943, the Tashme Youth Organization organized a baseball league backed financially by the Shinwa-kai. Four teams were formed: Asahis, Nippons, Wakabas and Arawashis. The teams consisted of single and married men from Tashme and workers from the nearby road camps. The league opened in June 1943 when the Arawashis and the Asahis met at the newly constructed ball field. Games were played on Wednesday and Sunday, competition was keen, and large crowds turned out to cheer their favourite teams.

Basketball

Basketball was popular among the students, who played in the "D" building during the winter months. READ MORE

Judo

Following Pearl Harbor and the forced closing of all judo clubs in British Columbia, Shigetaka Steve Sasaki was interned in Tashme where he kept the sport alive during the internment years with the largest judoka among the internment camps. Biography of Steve Sasaki

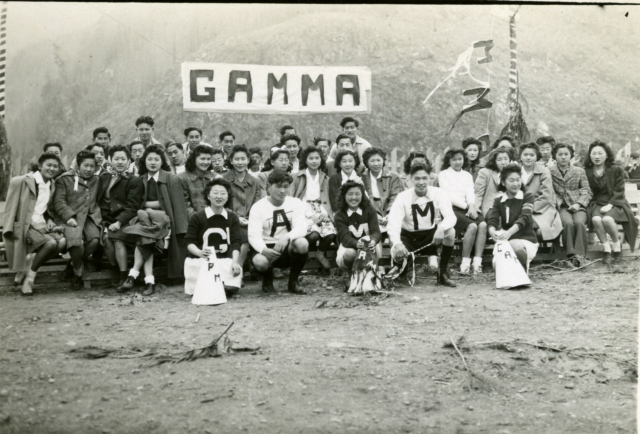

CLUBS

Tashme residents worked hard to keep young people occupied and engaged in constructive activities. And the young people themselves formed clubs and organizations to pursue common interests, socialize, and keep their spirits up.

Tashme Youth Organization

TYO consisted of young people over 16. It organized various activities including Boy Scouts, Girl Guides, and entertainment for the community. There were 144 Scouts, headed by Shige Yoshida. This was the largest troop of scouts among communities of similar size. Moreover, the Organization operated a small library consisting mostly of works of fiction. Because they were not allowed to have radios and could read only the weekly newspaper The New Canadian, the internees enjoyed reading many library books. Furthermore, the Organization planned concerts with both English and Japanese numbers. READ MORE

Scouts and Guides

Parents and adult leaders were eager to form Boy Scout and Girl Guide groups in Tashme, partly to provide continuity for the children and partly to keep them constructively occupied.

Shige Yoshida, who was part of the Boy Scout organization in Cumberland before being sent to Tashme, was the organizer and leader of the Tashme Boy Scouts. Cubmaster Vic Kadonaga led the Cub Scouts, with 48 young boys organized in eight groups of six to a cub pack. The Tashme Stars, similar to Girl Guides, was organized for the girls in the camp. READ MORE

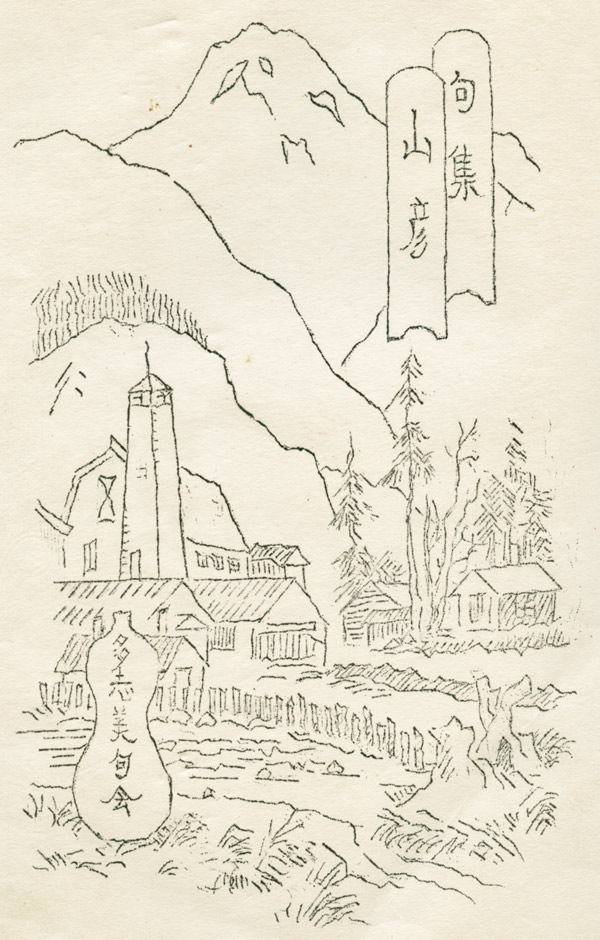

Tashme Poetry Society

Two booklets were donated by Mr and Mrs Fukeo Sameshima of Coaldale, Alberta, to the Nikkei National Museum in September of 2016. The booklets are simple and unpretentious, but as anthologies of poems composed by the members of the Tashme Poetry Society (Tashme kukai), they are remarkable records of the emotional history of Nikkei community from the internment era.

The two anthologies were compiled in 1945 and 1946 respectively. The 1945 edition, entitled Yamabiko or “The Echoes of the Mountains,” features 339 poems. Reikō, or “Spiritual Light” is the title of the 1946 edition, which comprises 319 poems. The anthologies provide a rare window to the emotions of the poets and their community during the internment era.

Movies

The Shinwa-kai sponsored the showing of movies as part of its program of recreation, sports and entertainment in Tashme. For two days every second weekend, the west side of the second floor of D building was converted to a community hall for the showing of movies. A 16 mm projector was housed in a gondola like structure that was suspended from the ceiling and hoisted to the ceiling when not in use. Seating was simple and consisted of long wooden benches.

Mr Kaizo Tsuyuki was responsible for organizing and operating the equipment for the movies. He brought in Hollywood and NFB films. But because not all movies were available in 16 mm format, the showing of English language movies was limited. So Mr Tsuyuki offered to show Japanese movies and movies from his extensive collection of home movies and silent Japanese movies.

He operated the projector and sound system and charged an admisstion fee of 10 cents for adults and five cents for children, a good part of which he donated to the Tashme Youth Organization for their community activities.

For the old Japanese silent movies Mr Tsuyuki not only operated the projector, he read the script and provided sound appropriate to the scenes being shown. The Japanese movies were shown so often that most of the movie goers knew the stories by heart. The audience would anticipate and shout out the dialogue as the movies were shown. Regardless of how often a movie played, there was always a full house. The audience had fun.

Concerts

There is a rich record of photographs of stage performances and performers at concerts which were held in the make shift community hall in D building. These concerts were organized and staged by TYO and were conducted in English and in Japanese. Those in Japanese were called Shibai. These concerts usually consisted of musical numbers featuring talented singers, singing groups and musicians who resided in Tashme. There were also stage plays and musicals staged by TYO members. Occasionally, performers from outside the camp were featured, again organized by TYO members. These concerts were very popular and were always very well attended. Both the Tashme performers and Tashme audiences enthusiastically supported these concerts because Tashme lacked the commercially supported theatre and entertainment of a normal village.

RADIOS WERE BANNED, BUT . . .

While radios (and cameras) were initially banned, the authorities sometimes looked the other way.

Though newspapers circulated freely, personal correspondence was censored and long-distance telephonic calls required RCMP or BCSC approval. Long wave radios were sometimes returned to those who requested them but in the mountains, reception was unreliable. In Tashme, some residents secretly kept a shortwave radio, listened to broadcasts from Japan, and distributed this information in an almost daily Japanese-language circular the Tasbme News. The Tashme News reported how the Japanese navy and army were winning the war; on 7 December 1943 it commemorated the second anniversary of the war by describing Japanese victories in the Pacific, Burma, and North China. It stated that construction of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere had progressed, that the 'Great Asian Race' .had over-thrown Britain and the United States, and that its long-cherished dream was coming true. The next day's issue included the emperor's message of December 1943 expressing his complete satisfaction with the recent battles, but urging the navy and air force to make greater efforts as the enemy was still trying to prevent Japan's dreams of constructing a 'New Order of the World' and creating a 'Greater Asia.' According to the Tashme News, U.S. claims of success were mere propaganda. Yet, in reporting one battle, the Tashme News presented conflicting views. A dispatch from Tokyo emphasized conditions favorable to the Japanese navy; a United States navy press release claimed American victories. To these reports was added a Reuter dispatch that the American navy had abandoned the operation because of heavy damages and casualties. Such news was designed to convince readers that the Japanese navy was winning and that the United States was merely releasing false propaganda. – From Mutual Hostages: Canadians and Japanese during Second World War, by Patricia Roy, et al. UT Press 1990. p129.

Page header: NNM 2010-80-2-12.