Tashme contained a variety of homes and functional buildings.

Houses

Three hundred forty-seven shacks, each meant to accommodate up to eight persons, were hastily constructed in a flat field east of the original farm buildings, between the Sumallo River to the south and a creek to the north.

BCSC standard houses measured approximately 14 feet by 25 feet and followed the same design in all the camps. They were built of rough shiplap lumber, milled at the nearby sawmill, which was nailed on the outside of a stud wall and covered with tar paper. Two shacks were joined by a common roofed area used to store firewood.

Each shack was subdivided into three sections: a living-kitchen area in the centre (about 9 x 14 feet); plus either one bedroom (8 x 14 feet), or two bedrooms (8 x 7 feet) on either side of the living-kitchen area. Bunk-style beds were often built on each side of the bedroom. There were no interior doors; curtains were used in the doorways for privacy. A woodstove and wooden sink were located along the back wall of the kitchen. A pot-belly woodstove provided heat. The approximate cost of each house was $145 in 1942 dollars.

List of materials used to construct the shacks.

Lighting was supplied by coal oil or kerosene lamps, which required regular cleaning. Later some residents switched to Coleman lanterns, which were brighter and cleaner.

There was no indoor plumbing. Four shacks shared a four-privy outhouse centrally located in back of two houses on two avenues.

The shacks were constructed in rows laid out approximately north-south along 10 avenues labeled 1st Avenue to 10th Avenue. To the south, the avenues intersected with a street named Tashme Boulevard. To the north, the avenues interested with a row of four bathhouses. A wood-slat boardwalk was constructed in front of the houses on both sides of the avenues. The sound of people walking with flat wooden Japanese sandals called geta to and from the bathhouses was heard every day.

Small families of up to four people occupied one side of a house while larger families occupied a whole house. Each family did its own cooking and washing.

The shacks were not insulated despite the freezing climate. During the first winter, the winter of 1942-1943, the rough ship lap lumber used to construct the shacks, still green, shrank as it dried, creating gaps and exacerbating the effects of the severe weather. Internees complained of having to chip away the ice which stuck their blankets to the walls in the morning when they woke.

Memorandum regarding Tashme shacks.

Apartments

An existing barn, known as C building, was adapted into 38 apartments on two floors and housed up to five persons per apartment. A communal kitchen was provided at one end of each floor. A bathhouse for apartment residents was built. A boiler house provided heat and hot water for the apartment.

The sheep barn attached to C building was renovated and subdivided into two areas. The half sharing a wall with C building, known as B building, was a dormitory that housed about 90 bachelors. The other half, known as A building, was used as school classrooms and as a church for the United Church congregation when it was not being used by the school.

E building was converted to an apartment for single women.????? A front section of this building was a barber shop, where haircuts cost 25 cents and a shampoo 10 cents.

Accommodations for most of the Caucasian BCSC staff were provided in a separate building. Staff lodgings were across the Sumallo River in apartments equipped with indoor plumbing, water, electricity, and a common room with a fireplace.

Some non-Japanese, including school teachers and church missionaries, lived among the Japanese residents. The women teachers of the United Church lived at 401 4th Avenue.

Bathhouses

To the north of the 10 avenues were four traditional Japanese bathhouses shared by the residents. Each bathhouse had two large Japanese ofuros for soaking and a smaller tub for drawing hot water for washing.

The bathhouses were segregated; one end was for men and boys and the other for women and children. The bathhouses were open daily from 4:00p.m. to 10:00p.m., and families used them according to a schedule assigned by address and days of the week.

Town Centre

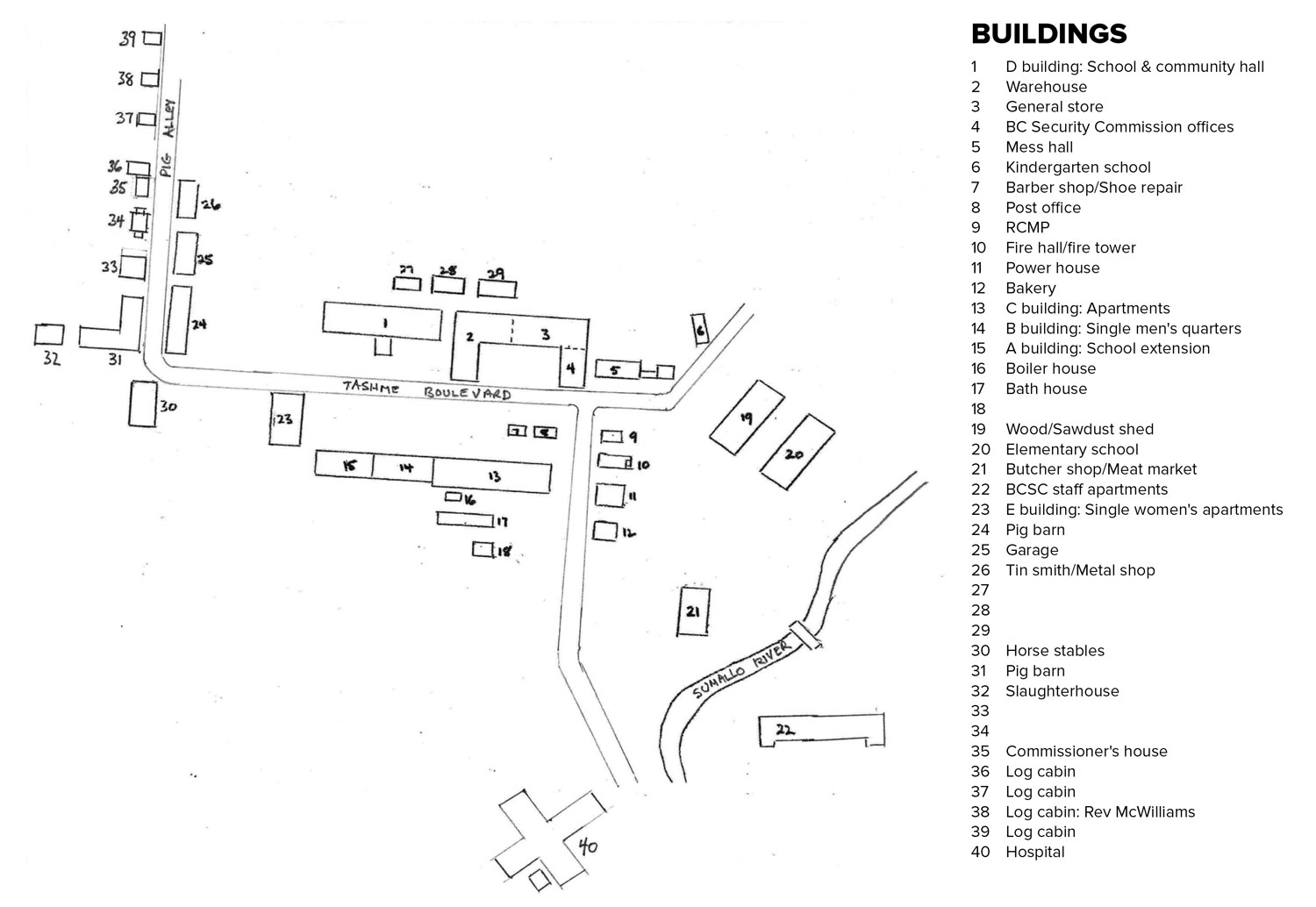

The BCSC provided all of the facilities of a self-sufficient small town. The town centre was a U-shaped building that housed the BCSC administrative offices, a general store, and a warehouse. Close by were smaller buildings for the RCMP detachment, a post office, a shoe repair shop, a bakery, a firehall, a power plant, a butcher shop/meat market and a mess hall. See map below.

An existing barn, known as D building, was remodeled into a school and community hall. The ground floor was divided into two large areas; one was a carpentry shop for the community, and the other was used as meeting rooms and school classrooms. The top floor was divided into two areas: one for classrooms and the other a large open area for community activities. This space also had movable partitions so it could be used for classrooms during the week and as an auditorium/gym on weekends. This arrangement lasted until a primary school was completed in 1944. See Education for details.

While families were responsible for their own cooking and meals, single men and workers away from their families were provided with a centrally located mess hall. The mess hall was subdivided into three areas. The middle section was the kitchen. One end was the dining hall for single Japanese Canadian men, while the other end was the dining hall for non-Japanese men and RCMP officers. Integration of diners was prohibited.

A 25 kilowatt power plant was installed to provide electricity for the centrally located buildings including the apartments, schools, hospital, general store, and commission offices. Its capacity was inadequate for providing electricity to the majority of internees residing in the shacks.

Farm Buildings

Most of the farm buildings that existed before Tashme was established were remodeled and adapted for living quarters. The supervisor for Tashme, who was appointed by the BCSC and acted as a non-elected mayor of Tashme, lived with his family in one of the log cabins along Pig Alley, the road leading from the town centre towards Hope. Similar log cabins accommodated other non-Japanese workers. For a time, Reverend McWilliams, a United Church minister who was instrumental in starting the high school, occupied one of these houses.

Other farm buildings were used to stable horses and raise and slaughter pigs. There were buildings for a blacksmith, a metal shop, and a garage for cars. There were two pig barns and a fenced-in field for the pigs. The meat was processed and sold at the meat market.

Hospital

A 50-bed hospital was constructed and staffed by a Caucasian and a Japanese doctor, along with Caucasian and mostly Japanese nursing staff. The cross-shaped building accommodated two large wings as wards for women and for men. There were also private wards, offices for the doctors, dentist, head nurse and optometrist, and an operating room, maternity ward, X-ray room, kitchen and laundry facilities. A morgue was built in the back of the hospital. Read more about health care.

Utilities and Infrastructure

A water reservoir was constructed on a mountain southwest of the town, upstream from the camp, and the water was carried by six 6-inch mains to the town, then distributed throughout the village. In the area of the shacks, water was piped to a common outdoor tap for every fourth house on each avenue.

A telephone line connected the camp to Hope. Use of telephone service was restricted to BCSC staff, the RCMP, and other government staff.

On the south side of the Sumallo River and east of the apartment for BCSC staff was a flat area used as a sports field that contained a baseball diamond. This area was used for outdoor community events.

There were three footbridges across the Sumallo River, one located near the meat market that connected to the non-Japanese staff apartment, a second farther east to connect the camp at the south end of 5th Avenue with the athletic field, and a third, near 10th Avenue, to connect the camp to the baseball field.

To the east of the camp were a crematorium and a garbage dump with an incinerator.

Sawmill

An existing sawmill stood north of the camp and beyond the guarded outpost that monitored traffic in and out of the camp and across the road that was to become the Hope-Princeton Highway. It was reconditioned and used to produce the lumber for the houses. The capacity of the mill was about 6,500 board feet per day. In addition to providing lumber for the construction, the sawmill processed trees into wood for fuel for Vancouver and other markets. See Employment for more information.

![2015-01-20-11.29.41[1]-(2)-web](http://tashme.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2015-01-20-11.29.411-2-web.jpg)